Information

Landmark: Tabby RuinsCity: Beaufort

Country: USA South Carolina

Continent: North America

Tabby Ruins, Beaufort, USA South Carolina, North America

The Tabby Ruins in Beaufort, South Carolina are remnants of early colonial and antebellum structures constructed with tabby concrete, a building material common in the southeastern coastal region. Tabby was made from burned oyster shells (lime), sand, water, and whole oyster shells as aggregate. This material was poured in layers into wooden molds, producing thick, durable walls that could withstand the humid coastal climate.

Historical Context:

Beaufort became a significant area for rice and indigo plantations during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Wealthy plantation owners used tabby for both functional and structural purposes, including kitchens, storage buildings, slave quarters, and sometimes fortifications.

The labor-intensive production of tabby involved enslaved Africans, who brought construction techniques adapted from West African traditions, combining them with European methods. This makes the ruins historically significant not only architecturally but culturally.

Key Sites in Beaufort:

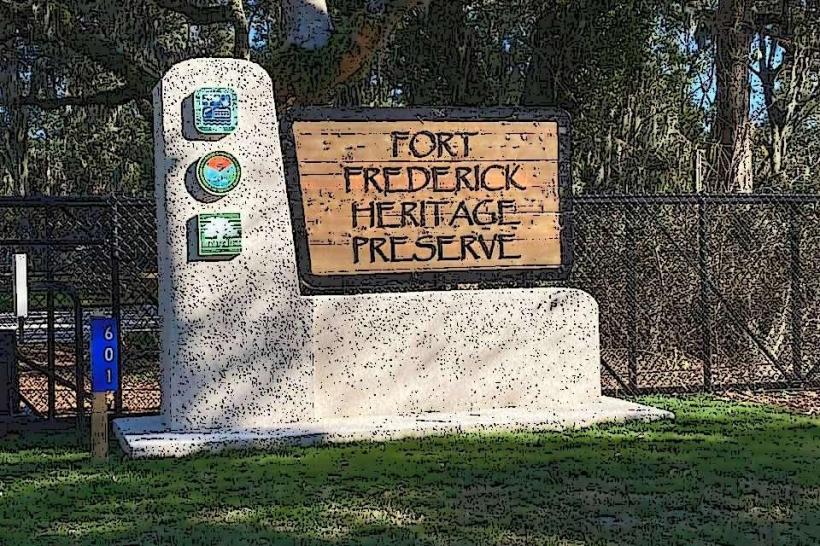

Fort Frederick Heritage Preserve:

Contains partially preserved tabby walls from an early colonial fort built in the mid-18th century.

The ruins include foundation walls, remnants of defensive structures, and outlines of former buildings.

The site reflects military strategies and coastal defenses used by early settlers.

Plantation Tabby Structures:

Surrounding areas of Beaufort include ruins of plantations like Simmons Plantation and Seaside Plantation, which preserve tabby foundations of kitchens, storage sheds, and slave quarters.

These ruins illustrate daily plantation operations, domestic life, and the forced labor system.

Construction Features:

Layered Walls: Tabby was poured in successive layers, with oyster shells providing reinforcement.

Durability: Many of the ruins’ walls survive partially because of tabby’s resistance to decay and saltwater corrosion.

Dimensions: Remaining walls often range from 1 to 2 feet thick, with partial fireplaces, windows, or door outlines visible.

Preservation and Visitor Access:

The ruins are protected as part of heritage preserves or state parks.

Visitors can walk along trails and see the tabby foundations and partial walls, often accompanied by interpretive signage detailing historical context.

Preservation focuses on stabilizing existing walls to prevent collapse while maintaining the authentic appearance of the ruins.

Cultural Significance:

Tabby ruins are a rare architectural record of colonial and antebellum life in coastal South Carolina.

They demonstrate a combination of European colonial techniques and African labor contributions.

The ruins are a tangible reminder of both the economic history of plantations and the human labor that built them.

These sites in Beaufort offer insight into early construction methods, colonial settlement patterns, and the region’s social history, while providing a visually striking connection to the past through the enduring tabby material.