Information

City: West New BritainCountry: Papua New Guinea

Continent: Australia

West New Britain, Papua New Guinea, Australia

West New Britain (WNB) is a province of Papua New Guinea located on the island of New Britain. It is defined by its massive oil palm industry, intense volcanic activity, and world-class marine biodiversity in Kimbe Bay. As of January 2026, it remains one of the fastest-growing provinces in the country due to agricultural expansion.

Historical Timeline

33,000+ Years Ago: Evidence of early human settlement at Kupona Na Dari near Kimbe, one of the oldest archaeological sites in the Pacific.

1914: Australia takes control of the region from Germany following the outbreak of WWI.

World War II: The province, particularly the Talasea and Cape Gloucester regions, saw heavy fighting between Japanese and Allied forces (including the US Marines).

1960s: The "Oil Palm Scheme" begins, leading to the establishment of large-scale plantations and the relocation of thousands of people from mainland PNG to WNB.

1976: West New Britain is officially established as a separate province from East New Britain.

Demographics & Population

The population is approximately 368,000 (2024 Census estimate).

Linguistic Diversity: Over 25 indigenous languages are spoken. Major ethnic groups include the Nakanai, Bakovi, Kove, Arowe, and Maleu.

Migration: WNB has a high proportion of "settlers"-non-indigenous residents from the Highlands and Sepik regions who moved for work in the oil palm industry.

Religion: Predominantly Roman Catholic, with significant Anglican and Evangelical communities.

Economy

Palm Oil: The economic backbone. WNB is the largest producer of palm oil in PNG, dominated by companies like New Britain Palm Oil Limited (NBPOL).

Logging: Active timber operations exist in the interior and along the south coast.

Tourism: Centered on high-end niche markets: scuba diving, sport fishing, and volcanic trekking.

Key Towns & Districts

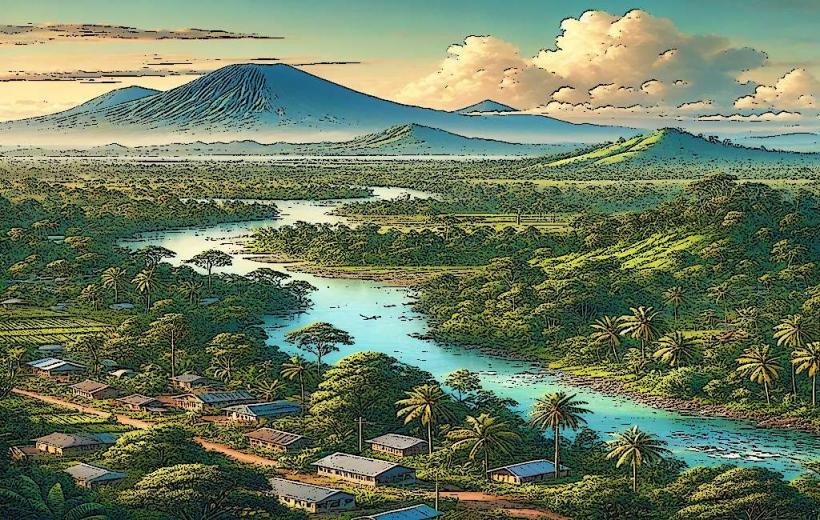

Kimbe: The provincial capital and commercial hub. It is a relatively modern town built around the palm oil trade.

Hoskins: Location of the main airport and several large plantation headquarters.

Bialla: A major agricultural town to the east, also focused on oil palm.

Kandrian: The main center on the remote and rugged south coast, accessible primarily by sea or small aircraft.

Top Landmarks & Attractions

Kimbe Bay: Globally famous among divers. It contains 60% of the coral species found in the entire Indo-Pacific. Key reefs include Vanessa’s Reef and Katherine’s Reef.

Walindi Plantation Resort: The province's premier eco-tourism destination and a world-renowned base for marine research.

Mount Ulawun: The highest volcano in PNG (2,334m) and one of the "Decade Volcanoes" due to its history of large, explosive eruptions.

Pangalu Hot Springs: Located in Talasea, featuring massive geysers and geothermal pools.

WWII Wrecks: Numerous submerged aircraft and ships remain in Kimbe Bay and near Talasea, including a well-preserved Lockheed Ventura.

Transportation Network

Air: Hoskins Airport (HKN) is the gateway, with daily flights to Port Moresby and Lae.

Road: The northern coast is connected by a main highway between Kimbe and Bialla. However, there is no road link between the north and south coasts; the interior remains an impenetrable mountain range.

Sea: Coastal shipping and "banana boats" are the only way to reach southern settlements like Kandrian and Gloucester.

Safety & Health

Volcanic Risk: WNB is highly active. Mount Ulawun and the Garbuna Group are under constant monitoring by the Rabaul Volcanological Observatory.

Security: Ethnic tensions between indigenous landowners and migrant plantation workers occasionally lead to localized unrest. Standard precautions against petty crime in Kimbe are necessary.

Health: Malaria is endemic and highly prevalent in the plantation areas. The Kimbe General Hospital is the primary facility, though private clinics in Walindi are preferred by travelers.

Local Cost Index

1 Espresso (Walindi/Kimbe): ~K12 – K15 ($3.00 – $3.75)

1 PMV (Bus) Fare (Kimbe to Hoskins): ~K5 – K10 ($1.25 – $2.50)

1 Guided Dive: ~K300 – K500 ($75 – $125)

Facts & Legends

A verified geographical fact is that New Britain island is roughly the same size as Taiwan, yet WNB contains some of the least explored primary rainforest on Earth. Local legend among the Nakanai people speaks of the "Galum," forest spirits that guard the deep limestone caves of the interior, believed to be the reason why those who enter the deep bush without a traditional "welcome" often vanish.