Information

Landmark: Bahia PalaceCity: Marrakech

Country: Morocco

Continent: Africa

Bahia Palace, Marrakech, Morocco, Africa

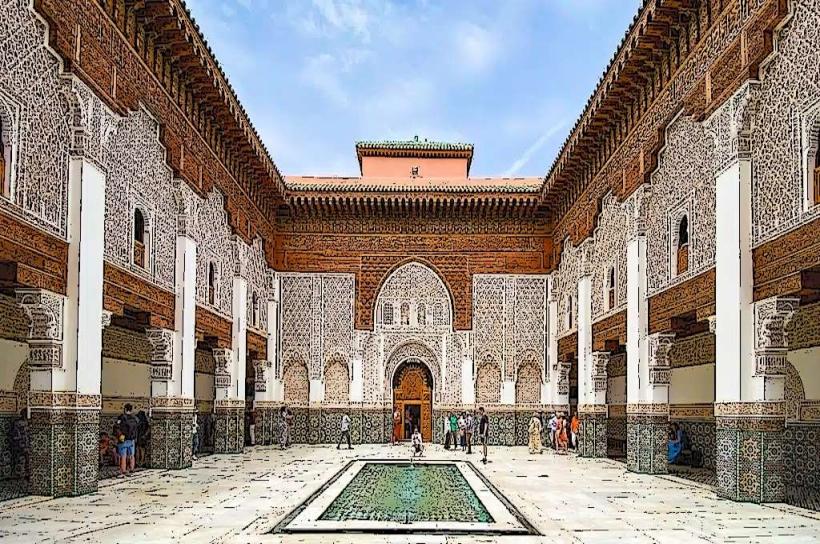

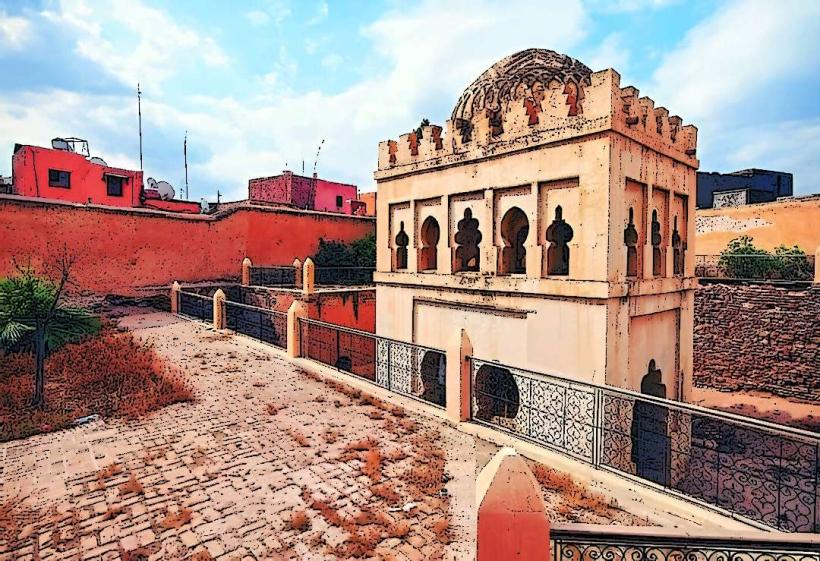

The Bahia Palace is a 19th-century palace complex located in Marrakech, Morocco. It was constructed between 1866 and 1867.

Visual Characteristics

The palace covers approximately 8 hectares (20 acres) and features a complex layout of courtyards, gardens, and private apartments. Construction materials include zellij tilework, carved stucco, and cedarwood. The dominant colors are blues, greens, and yellows, with intricate geometric patterns. The architecture blends Islamic and Moroccan styles, with influences from Andalusian design.

Location & Access Logistics

The Bahia Palace is situated in the Kasbah district of Marrakech. It is approximately 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) south of Jemaa el-Fnaa square. Access is via Rue Riad Zitoun Jdid. Limited street parking is available in the vicinity, and taxis are a common mode of transport. Public bus lines 1, 4, and 10 stop within a 500-meter radius.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Construction was initiated by Si Moussa, Grand Vizier of the Sultan, and completed by his successor, Ba Ahmed, in 1867. The palace was intended as a residence for Ba Ahmed and his harem, and as a demonstration of his wealth and power. The name "Bahia" translates to "brilliance" or "beauty."

Key Highlights & Activities

Visitors can explore the Grand Courtyard, the harem quarters (including the apartments of the four wives and 24 concubines), and the Grand Reception Hall. Photography is permitted within the palace grounds. Guided tours are available, providing historical context and architectural details.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available on-site. Limited shaded areas are present within the courtyards and gardens. Cell phone signal (4G/5G) is generally available. Food vendors and cafes are located outside the palace walls, within a 100-meter radius.

Best Time to Visit

The best time of day for photography is in the morning, between 9:00 AM and 11:00 AM, when natural light illuminates the courtyards. The most favorable months for visiting are from March to May and September to November, avoiding the peak summer heat.

Facts & Legends

A notable feature is the Grand Courtyard, paved with marble and surrounded by arcades. It is said that Ba Ahmed commissioned the palace to impress a favorite concubine, though historical records suggest it was primarily a statement of his political standing.

Nearby Landmarks

- El Badi Palace (0.8km Northwest)

- Saadian Tombs (1.2km West)

- Koutoubia Mosque (1.8km Northwest)

- Jemaa el-Fnaa (2.0km Northwest)