Information

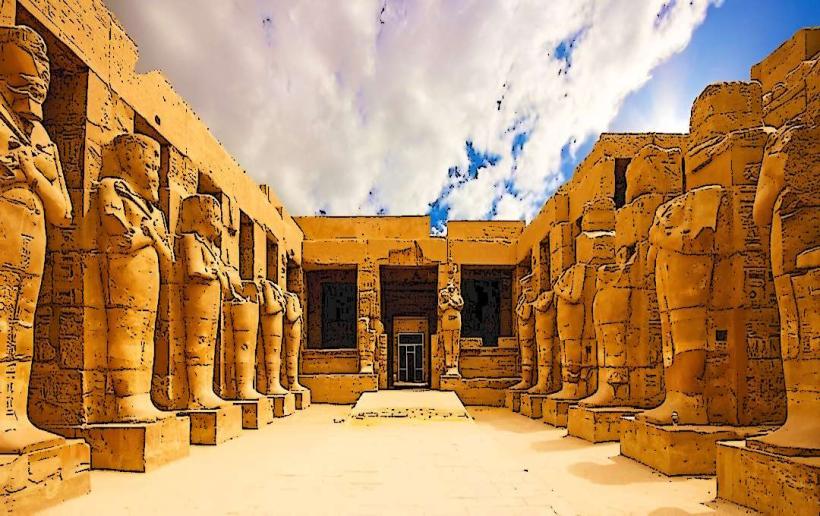

Landmark: Colossi of MemnonCity: Luxor

Country: Egypt

Continent: Africa

Colossi of Memnon, Luxor, Egypt, Africa

The Colossi of Memnon are two massive stone statues of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, situated on the west bank of the Nile River near Luxor, Egypt.

Visual Characteristics

Each statue stands approximately 18 meters (60 feet) tall and is carved from a single block of quartzite sandstone. They depict Amenhotep III seated on his throne, with his hands resting on his knees. The statues are weathered, with significant erosion visible, particularly on the upper portions. Originally, they were part of a larger temple complex, the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III, which has largely disintegrated over time.

Location & Access Logistics

The Colossi of Memnon are located approximately 18 kilometers (11 miles) southwest of Luxor city center. Access is typically via taxi or private car from Luxor. Public transport options are limited; local minibuses may pass nearby, but require a walk to the site. Parking is available on an unpaved area adjacent to the statues.

Historical & Ecological Origin

These statues were erected around 1350 BCE during the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. They served as guardians of the entrance to Amenhotep III's mortuary temple. The sandstone was quarried from Gebel el-Silsila, a site approximately 60 kilometers (37 miles) south of Luxor.

Key Highlights & Activities

Observation of the scale and craftsmanship of the ancient statues is the primary activity. Visitors can walk around the base of the statues. Photography is permitted. No guided tours are permanently stationed at the site, though local guides may offer services.

Infrastructure & Amenities

There are no permanent restroom facilities or shade structures at the immediate site. Small stalls selling water and souvenirs are often present. Cell phone signal is generally available (4G).

Best Time to Visit

For optimal lighting conditions for photography, early morning or late afternoon is recommended. The months of October through April offer the most comfortable temperatures for outdoor exploration. Avoid midday during the summer months due to high temperatures.

Facts & Legends

One of the statues was famously known as the "singing statue" in antiquity. After an earthquake in 27 BCE damaged the upper portion, the statue reportedly emitted a sound at sunrise, attributed to the rising sun heating the stone. Roman emperors visited to hear this phenomenon. The statue was later repaired by Septimius Severus in the 3rd century CE, and the singing ceased.

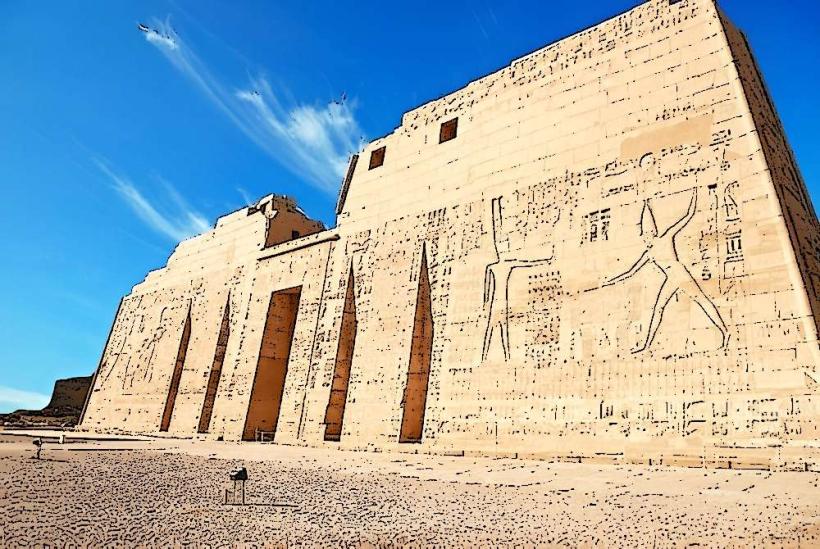

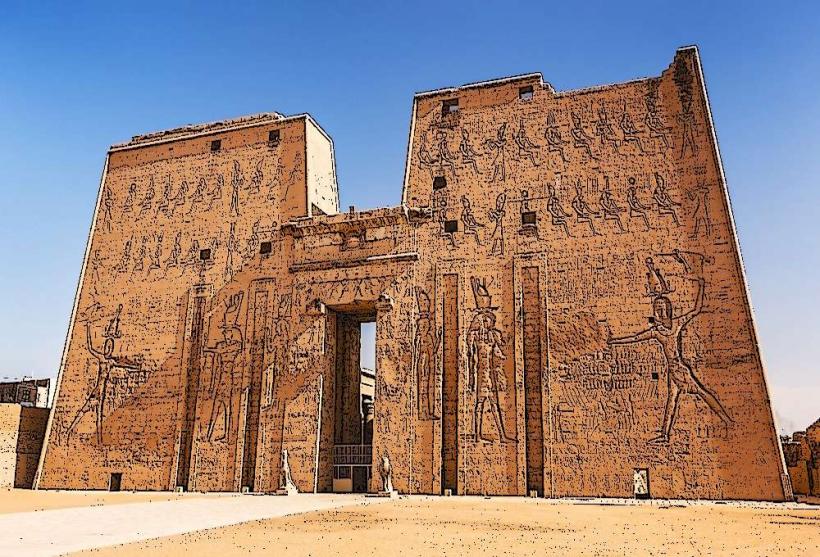

Nearby Landmarks

- Mortuary Temple of Seti I (2.5km Northeast)

- Valley of the Queens (4km Southwest)

- Ramesseum (4.5km Northeast)

- Medinet Habu (5km Northeast)