Information

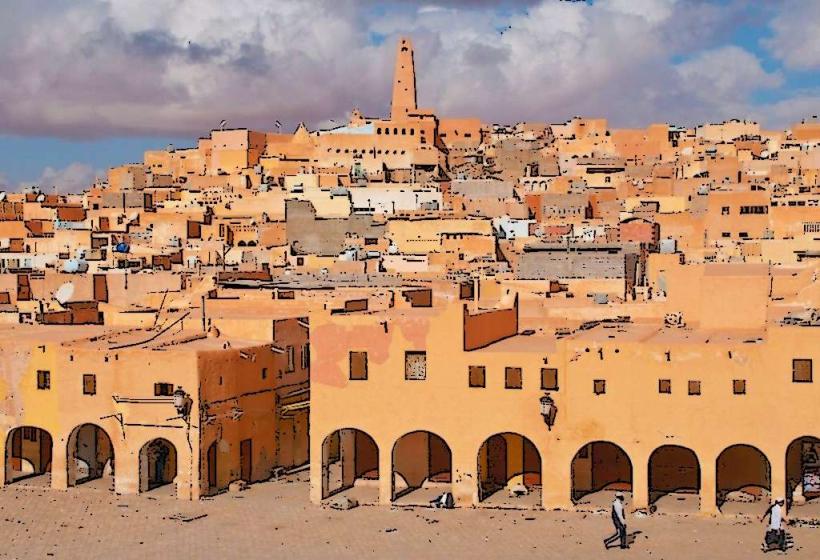

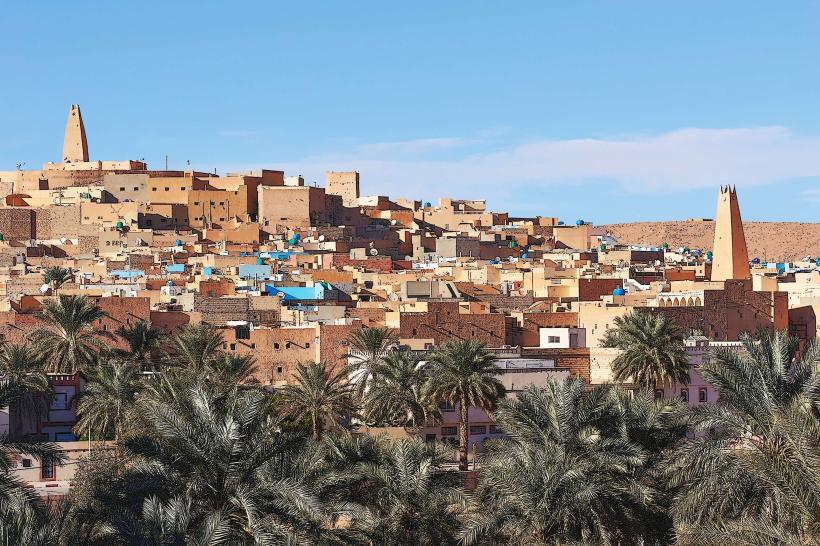

Landmark: M'zab ValleyCity: Ghardaia

Country: Algeria

Continent: Africa

M'zab Valley, Ghardaia, Algeria, Africa

The M'zab Valley is a prehistoric glacial valley located in the northern Sahara Desert of Algeria. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site recognized for its unique vernacular architecture and the traditional way of life of its inhabitants.

Visual Characteristics

The valley features a series of fortified towns (ksour) constructed from local red earth and stone. Buildings are typically cubic with flat roofs, designed for thermal regulation. The dominant color palette is ochre and red, reflecting the surrounding desert landscape. The architecture is characterized by narrow, winding streets and communal spaces.

Location & Access Logistics

The M'zab Valley is situated approximately 500 kilometers south of Algiers. Access is primarily via National Road RN1, which connects Algiers to Tamanrasset. The nearest major city is Ghardaïa, which has an airport (Ghardaïa Airport - GHA) with domestic flights. Within the valley, travel between the five main ksour (Ghardaïa, Beni Isguen, Melika, Bounoura, and El Atteuf) is typically done by private vehicle or taxi. Parking is generally available outside the historic centers of the towns.

Historical & Ecological Origin

The M'zab Valley was settled in the 11th century by Ibadites fleeing persecution. The architecture reflects their communal and religious principles, with a focus on defense and resource management. The valley's geological origin is a dry riverbed, a remnant of a past wetter climate, now characterized by arid conditions and sparse vegetation.

Key Highlights & Activities

Exploration of the five ksour, including Ghardaïa's old town and its minaret. Visiting the market in Beni Isguen. Observing traditional Ibadite religious practices (respectful observation is required). Walking through the palm groves and irrigation systems. Photography of the distinct architectural style.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available in designated tourist areas and some cafes. Shade is provided by narrow streets and building overhangs. Cell phone signal (4G) is generally available in the main towns. Food vendors and restaurants are present in Ghardaïa and Beni Isguen.

Best Time to Visit

The best time to visit is during the cooler months, from October to April. Daytime temperatures can exceed 40°C in summer. For photography, early morning and late afternoon offer softer light and longer shadows, enhancing the architectural details.

Facts & Legends

The M'zab Valley's unique urban planning is designed to maximize shade and minimize heat exposure. Each ksar has a central mosque with a tall, slender minaret that also served as a watchtower. A local legend states that the palm trees in the valley were planted by the first settlers to provide sustenance and shade, symbolizing their resilience.

Nearby Landmarks

- Ghardaïa Market (0.1km West)

- Beni Isguen Old Town (2km South)

- Melika Ksar (3km South)

- Bounoura Ksar (4km South)

- El Atteuf Ksar (5km South)