Information

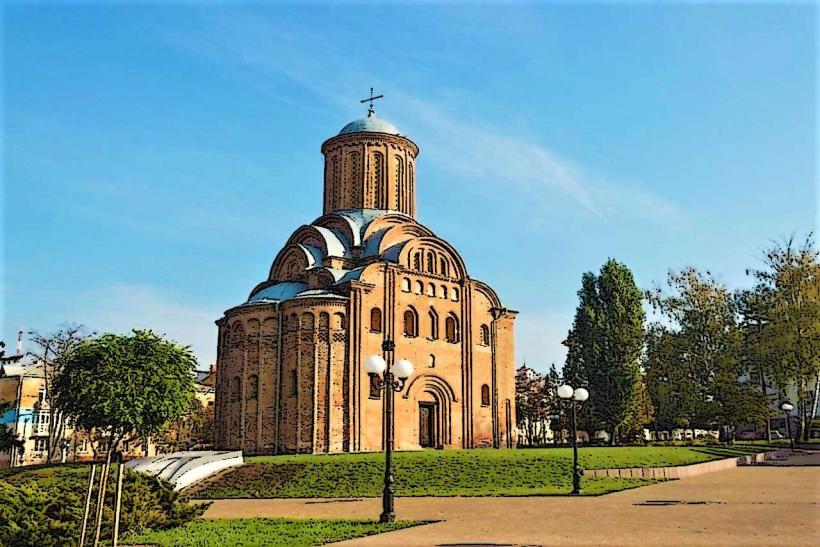

Landmark: Saviour-Transfiguration ChurchCity: Chernihiv

Country: Ukraine

Continent: Europe

Saviour-Transfiguration Church, Chernihiv, Ukraine, Europe

The Saviour-Transfiguration Church is an Orthodox church located in Chernihiv, Ukraine. It is one of the oldest surviving churches in the city.

Visual Characteristics

This stone church features a single dome and is constructed from white limestone. Its architectural style is characteristic of Kievan Rus' period churches, with a simple, rectangular plan and a prominent apse. The exterior walls are largely unadorned, emphasizing the structural form.

Location & Access Logistics

The church is situated within the Chernihiv Dytynets (fortress) complex, located at the western edge of the historic city center. It is accessible by foot from the main city streets. Parking is available in designated areas around the Dytynets, approximately 0.2km East of the church. Public transport routes terminate at the city center, requiring a short walk to reach the site.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Construction of the Saviour-Transfiguration Church began in the 11th century, likely between 1030 and 1050 AD. It is attributed to Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich. The church served as a cathedral and a burial site for Chernihiv princes.

Key Highlights & Activities

Visitors can observe the church's ancient architecture and interior frescoes. Photography is permitted inside the church. The church is part of the Chernihiv Dytynets historical complex, which can be explored.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available within the Dytynets complex, approximately 0.1km North of the church. Limited shade is provided by surrounding trees. Cell phone signal (4G/5G) is generally available. No on-site food vendors are present; options are available in the city center.

Best Time to Visit

For optimal interior lighting, visit between 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM. The months of May through September offer the most stable weather conditions for exploring the exterior and surrounding grounds.

Facts & Legends

During the Mongol invasion of 1239, the church was damaged but subsequently repaired. A local legend suggests that a hidden treasure belonging to the Chernihiv princes is buried beneath the church, though no evidence supports this claim.

Nearby Landmarks

- Chernihiv Collegium (0.1km Northeast)

- St. Anthony's Caves (0.8km Southwest)

- Bohdan Khmelnytsky Park (0.3km Southeast)

- National Architecture and History Museum "Ancient Chernihiv" (0.15km East)