Information

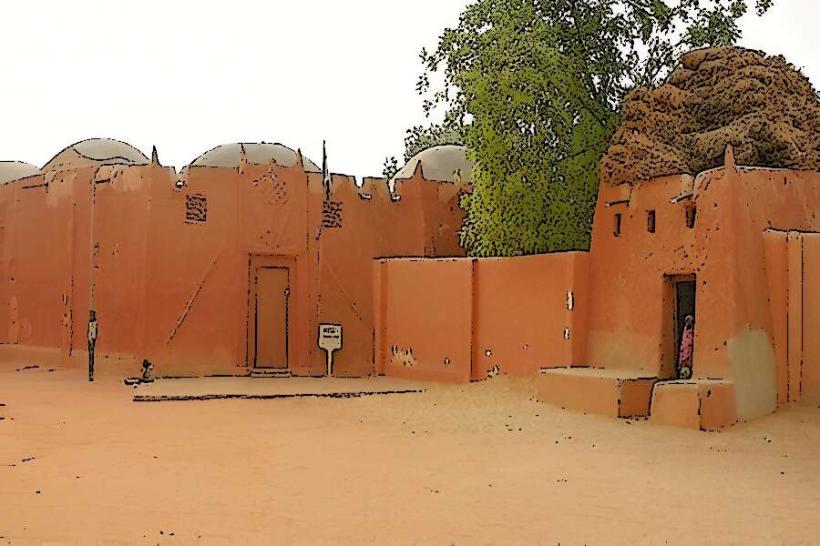

Landmark: Sokoto City WallsCity: Sokoto

Country: Nigeria

Continent: Africa

Sokoto City Walls, Sokoto, Nigeria, Africa

The Sokoto City Walls are a historic and symbolic fortification built to protect and define the ancient city of Sokoto, the capital of the Sokoto Caliphate in northwestern Nigeria. These walls not only served a military purpose but also represented the organized structure and cultural prestige of one of West Africa’s most influential Islamic empires.

1. Historical Background

Construction of the Sokoto City Walls began around 1809, shortly after the founding of the Sokoto Caliphate by Shehu Usman dan Fodio, the leader of the Islamic jihad that overthrew the Hausa states. The Caliphate became one of the largest and most organized Islamic states in Africa in the 19th century.

His son, Sultan Muhammad Bello, who succeeded him and ruled from 1817 to 1837, is widely credited with commissioning the construction of the walls as part of his effort to:

Fortify Sokoto as the Caliphate’s political and spiritual capital.

Protect the growing city from external threats like rival kingdoms, raiders, and colonial encroachment.

Organize the city’s growth through a system of controlled entry points and inner administrative zones.

The walls were completed by the early 1820s, enclosing the core of Sokoto with a network of defensive structures and gates.

2. Architectural Features

The Sokoto City Walls were built using traditional Hausa-Fulani architecture and local materials:

Sun-dried mud bricks, laterite, and stone.

The walls stood several meters high and were thick enough to withstand attacks.

Defensive ramparts and watch towers were located at intervals.

The structure was reinforced over time, especially near the main gates.

The original wall enclosed the administrative and spiritual heart of Sokoto, including:

The Sultan’s Palace

The central mosque

Markets and residential areas for scholars and administrators

3. The Eight City Gates (Kofa)

The city walls were equipped with eight gates, known as “Kofa”, each functioning as a controlled entry point into the city. Each gate had social, administrative, and sometimes spiritual significance.

The gates included:

Kofar Rini – leading toward the Rini settlement and caravan routes

Kofar Dundaye – connected to nearby farming communities

Kofar Atiku – likely named after an early Sultan or noble figure

Kofar Aliyu Jedo – associated with a famous Fulani scholar and warrior

Kofar Tarammniya

Kofar Kware

Kofar Marke

Kofar Kade

Each gate was guarded and functioned as a customs point, where goods could be inspected and levies collected. These gates also helped monitor who entered and left the city, adding to its internal security.

4. Cultural and Strategic Importance

The walls were a physical manifestation of the Caliphate’s authority and sophistication. They allowed for:

Urban planning within a fortified zone

Efficient administration of the Caliphate’s core region

Military preparedness in times of war

Protection of Islamic scholars and sacred spaces

Additionally, the structure symbolized the unity of the Ummah (Muslim community) in the region and served as a center for Islamic jurisprudence, diplomacy, and scholarship.

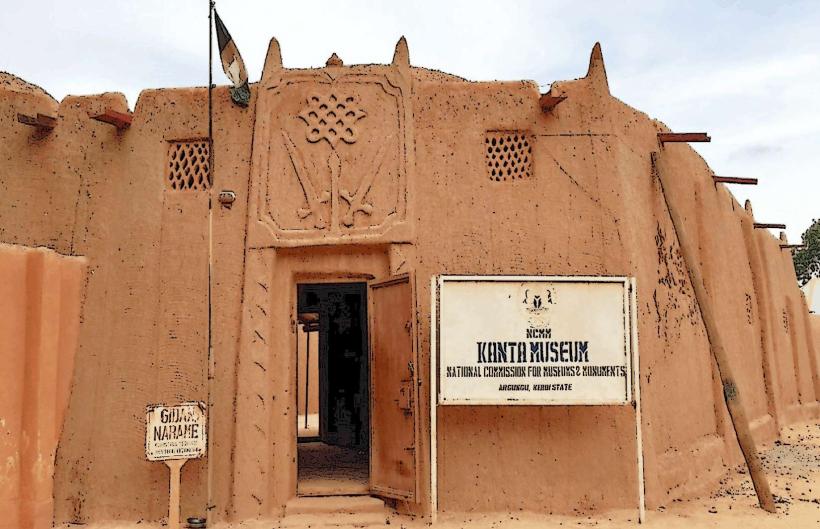

5. Modern State and Preservation

Today, only sections of the original city walls remain, due to:

Urban expansion

Neglect over the colonial and post-colonial periods

Natural erosion and lack of conservation infrastructure

However, some gates, such as Kofar Kware and Kofar Dundaye, are still standing and are recognized by historians and cultural authorities as vital pieces of Nigerian heritage. Local communities continue to show respect and reverence for these sites, particularly during religious festivals or public processions.

There have been calls for restoration and preservation, especially from the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), as well as local historians who want to see the walls protected and potentially listed as a national monument.

6. Visiting the Site

Location: Central Sokoto, surrounding the old quarters near the Sultan’s Palace and main mosque.

Best Time to Visit: During cultural festivals like Eid or the Maulud (Prophet’s Birthday), when traditional pageantry occurs near some of the gates.

Tourism Tips: Visitors are advised to hire local guides familiar with the history of the Caliphate and its geography.

7. Legacy

The Sokoto City Walls remain an enduring symbol of:

Islamic urban design

Post-jihad political organization

The centralized leadership of the Caliphate

The cultural sophistication of northern Nigerian societies in the 19th century

Though in partial ruin, they are still among the most important historical and cultural relics in Nigeria, representing an era of scholarship, governance, and spiritual leadership that had deep influence across West Africa.