Information

Landmark: The Baths of DiocletianCity: Rome

Country: Italy

Continent: Europe

The Baths of Diocletian, Rome, Italy, Europe

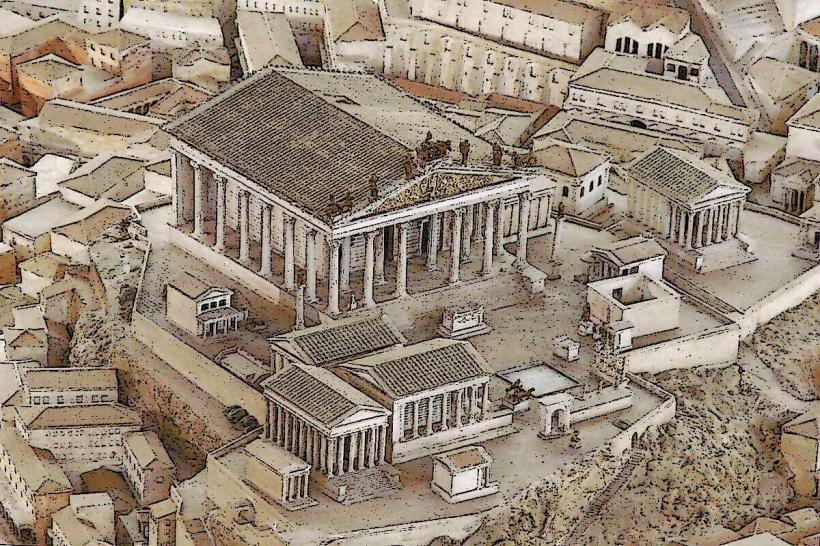

The Baths of Diocletian (Terme di Diocleziano) were the largest and most luxurious public baths in ancient Rome. Today, the site functions as one of the four branches of the National Roman Museum and houses the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri.

Visual Characteristics

The complex covers an area originally spanning 13 hectares. The remains are characterized by massive brickwork vaults and soaring halls. Much of the original structure was repurposed; the tepidarium and frigidarium were converted into a church, while other sections became a charterhouse. The site features a massive 16th-century cloister and a central courtyard filled with ancient funerary altars and sculptures.

Location & Access Logistics

Address: Via Enrico de Nicola, 78, 00185 Roma RM.

Transport: Directly adjacent to Roma Termini (Metro Lines A and B, plus main rail lines).

Access: Requires a paid ticket (often sold as a combined pass for all National Roman Museum sites). The Basilica section is free to enter.

Operating Hours: Tuesday–Sunday, 09:30 to 19:00. Closed on Mondays.

Historical Origin

Construction began in 298 AD under Emperor Diocletian and was completed in 306 AD. The complex could accommodate over 3,000 bathers simultaneously. Like the Baths of Caracalla, they ceased functioning in 537 AD when the aqueducts were cut during the Siege of Rome. In 1561, Michelangelo was commissioned to transform the ruins into a church and a monastery.

Key Highlights & Activities

The Michelangelo Cloister: One of the largest cloisters in Italy, measuring 100 meters on each side, containing over 400 archaeological finds.

Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri: A unique church designed by Michelangelo that utilizes the original soaring height and granite columns of the Roman frigidarium.

The Meridian Line: A 17th-century solar clock embedded in the church floor, used to verify the Gregorian calendar.

The Aula Ottagona: An octagonal hall (formerly part of the baths) that now displays ancient bronze sculptures, located a short walk from the main entrance.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Accessibility: Most of the museum and the church are wheelchair accessible with ramps and level floors.

Services: Bookstore, restrooms, and lockers are available at the museum entrance.

Connectivity: 5G signal is excellent due to its proximity to the Termini transit hub.

Best Time to Visit

The museum is rarely as crowded as the Colosseum or Vatican. Morning is ideal for experiencing the quiet atmosphere of the Michelangelo Cloister.

Facts & Legends

The project was so massive that thousands of Christian slaves were reportedly forced to work on its construction. This legend led to the site being dedicated to "Angels and Martyrs" during the Renaissance.

Nearby Landmarks

National Roman Museum - Palazzo Massimo: 0.2km South.

Piazza della Repubblica: Directly adjacent West.

Santa Maria della Vittoria (Ecstasy of St. Teresa): 0.4km West.

National Museum of Musical Instruments: 1.5km East.