Information

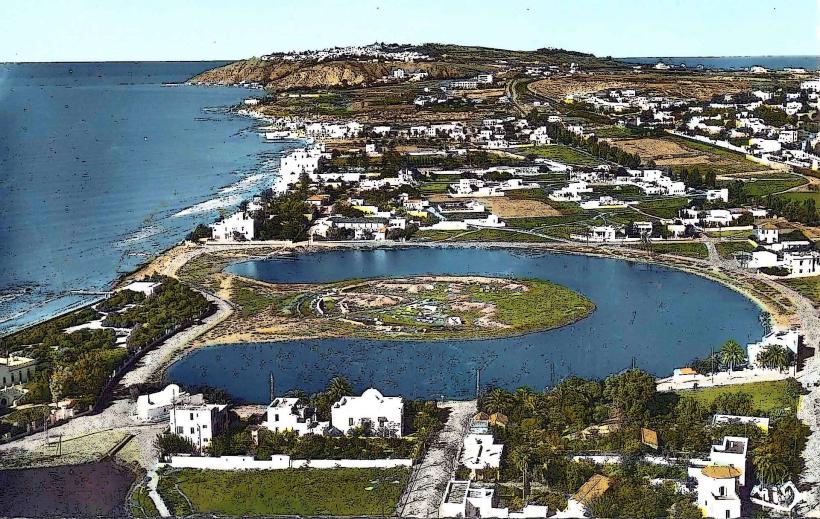

Landmark: Carthage AqueductCity: Carthage

Country: Tunisia

Continent: Africa

Carthage Aqueduct, Carthage, Tunisia, Africa

The Carthage Aqueduct was a monumental Roman engineering project designed to supply water to the city of Carthage, located in present-day Tunisia. Built during the Roman period after the destruction and subsequent rebuilding of Carthage, the aqueduct is one of the most significant feats of Roman hydraulic engineering in North Africa.

Here is a detailed overview:

Historical Context

After the Romans destroyed Carthage in 146 BCE during the Third Punic War, they later refounded it as a Roman colony under Julius Caesar and Augustus. Carthage grew into an important city in Roman Africa, eventually becoming the capital of the province of Africa Proconsularis. As the city expanded in size and prestige, a reliable supply of fresh water became essential to support its population, public baths, fountains, and agricultural needs.

Construction of the Carthage Aqueduct began during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117–138 CE) and was expanded and completed under Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161 CE).

Purpose

The aqueduct was built to bring water from freshwater springs located in the foothills of the Djebel Zaghouan mountains, approximately 90 kilometers (56 miles) southwest of Carthage. Chief among these springs was at Zaghouan, which became the starting point of the aqueduct.

Structure and Engineering

The Carthage Aqueduct combined several typical Roman engineering features:

Sources: The main water source was the spring at Zaghouan, but secondary springs from areas like Jouggar were also tapped into the system.

Length: The full system stretched around 132 kilometers (82 miles) when considering all the branches and connections to various reservoirs and cisterns along the way.

Construction Style:

Much of the aqueduct ran underground in covered channels.

Where the terrain required, especially near valleys and lowlands, the water was carried across massive series of arched bridges (arcades).

Some arcades reached up to 20 meters (about 66 feet) in height, showing the skill of Roman engineers in adapting to the landscape.

Materials: The aqueduct was mainly built of stone masonry combined with Roman concrete (opus caementicium), a strong and durable material. Waterproof cement (opus signinum) was often used to line the water channels.

Gradient: Like most Roman aqueducts, it maintained a very gentle and continuous gradient to allow gravity-driven flow without the need for mechanical pumping.

Key Features

Zaghouan Water Temple (Temple des Eaux): At the source near Zaghouan, the Romans built a beautiful monumental nymphaeum (a type of sacred fountain or temple dedicated to water nymphs) called the Temple of Water. It served both as a practical reservoir and a religious site venerating the life-giving springs.

Distribution: Upon reaching Carthage, the water was stored in large cisterns and distributed to public baths (such as the massive Baths of Antoninus), fountains, and private homes.

Maintenance Structures: The aqueduct had inspection shafts (putei) and maintenance access points regularly along its course, allowing workers to clear debris and repair any damages.

Decline

With the gradual decline of Roman authority in North Africa and the onset of Vandal invasions in the 5th century CE, the maintenance of the aqueduct system suffered. Eventually, during later Byzantine and Arab periods, the system fell into disrepair and ceased functioning fully.

Archaeological Remains

Today, impressive remains of the Carthage Aqueduct can still be seen:

The long arcades stretching across open countryside, particularly near the village of Mohammedia.

Sections of underground channels.

Parts of the cisterns and reservoirs in Carthage itself.

The monumental remains of the Water Temple at Zaghouan, restored and studied extensively.

These ruins remain a testament to Roman mastery of civil engineering and the importance of water management in sustaining ancient urban centers.

If you want, I can also describe the Temple of Water or the Baths of Antoninus, which were both closely connected to the aqueduct's purpose.