Information

Landmark: Historic WestvilleCity: Columbus City

Country: USA Georgia

Continent: North America

Historic Westville, Columbus City, USA Georgia, North America

Historic Westville is a living history museum located in Columbus, Georgia, USA. It reconstructs 1850s Georgia life through authentic buildings and demonstrations.

Visual Characteristics

The site features approximately 30 historically accurate structures, including log cabins, a general store, a blacksmith shop, and a church. Buildings are constructed from wood, brick, and stone, reflecting mid-19th-century vernacular architecture. The grounds are landscaped with period-appropriate flora, and a small creek runs through the property.

Location & Access Logistics

Historic Westville is situated at 5071 Westville Road, Columbus, Georgia. It is approximately 8 kilometers (5 miles) west of downtown Columbus. Access is via Westville Road, which connects to US Highway 80. Ample free parking is available on-site. Public transport options are limited; the nearest bus route is several kilometers away.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Historic Westville was established in 1970 as a project to preserve and interpret the history of Western Georgia. The buildings are either original structures relocated to the site or precise reconstructions based on historical research. The land itself is part of the Piedmont region, characterized by rolling hills and deciduous forests.

Key Highlights & Activities

Visitors can observe costumed interpreters demonstrating crafts such as blacksmithing, weaving, and cooking. Guided tours are available daily. Specific demonstrations occur at scheduled times throughout the day. The site also includes a nature trail along the creek.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available in the visitor center and near the main village area. Shaded areas are provided by trees and some covered porches on the buildings. Cell phone signal (4G) is generally available. A small gift shop sells period-inspired items; food vendors are not typically present on-site, but picnic tables are available.

Best Time to Visit

The best time for photography is during the morning or late afternoon when the sun angle provides softer light. The most pleasant weather for visiting is from March to May and September to November, avoiding the heat and humidity of summer. No specific tide requirements apply.

Facts & Legends

A unique aspect of Historic Westville is its collection of authentic period tools and artifacts, many of which are still used in demonstrations. One building, the "Old Schoolhouse," is said to have been a gathering place for local community events dating back to the late 1800s.

Nearby Landmarks

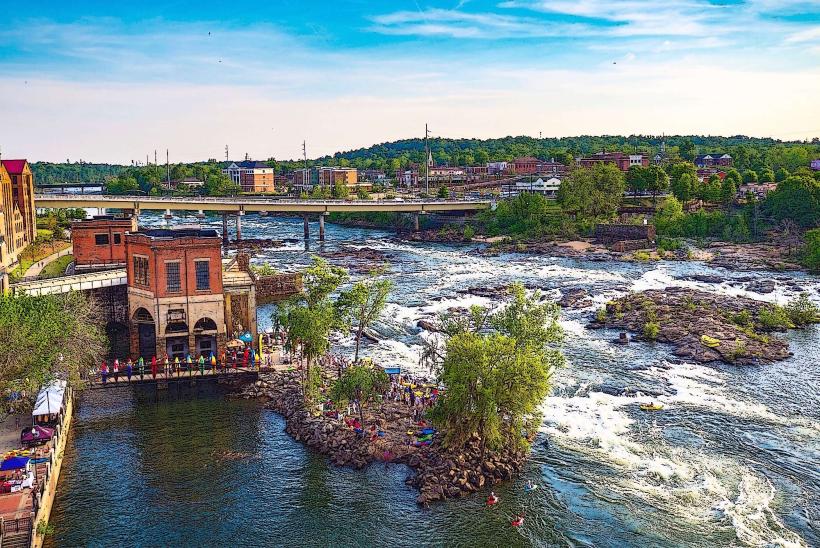

- Columbus Riverwalk (3.5km East)

- National Civil War Naval Museum at Port Columbus (4.0km East)

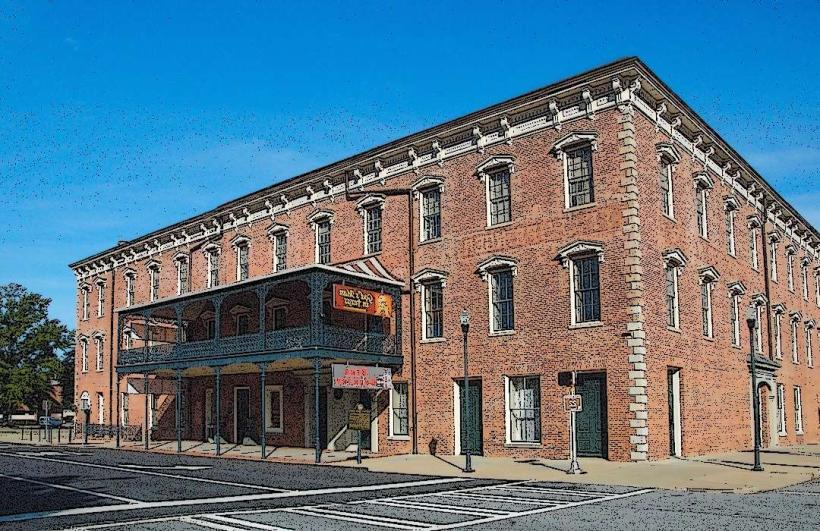

- Springer Opera House (5.0km East)

- Iron Works Park (4.5km East)