Information

Landmark: Citadel of SaladinCity: Cairo

Country: Egypt

Continent: Africa

Citadel of Saladin, Cairo, Egypt, Africa

The Citadel of Saladin is a medieval Islamic-era fortification situated on the Mokattam Hills overlooking Cairo, Egypt.

It was constructed by Ayyubid Sultan Saladin between 1176 and 1183 CE as a defense against Crusader forces.

Visual Characteristics

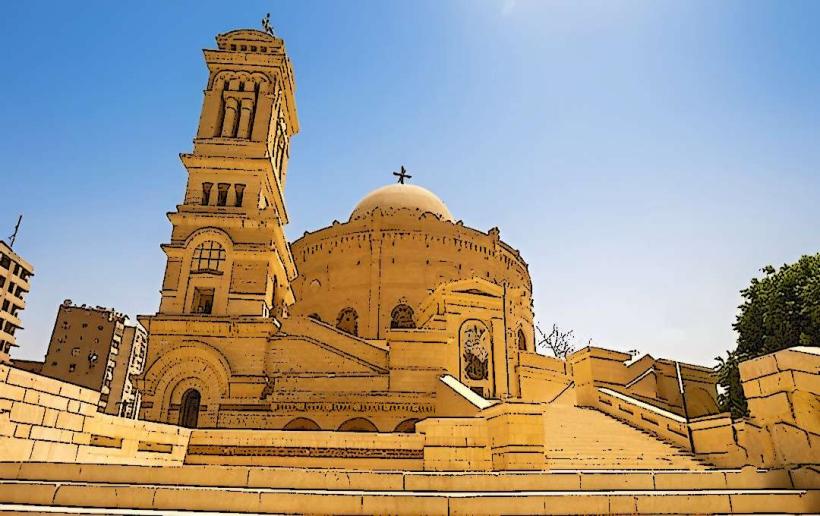

The Citadel is primarily constructed from limestone. Its walls and towers exhibit a robust, military architecture characteristic of the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods. Key structures within the complex include the Mosque of Muhammad Ali Pasha, built with Ottoman-style domes and minarets, and the Al-Nasir Muhammad Mosque, featuring Mamluk architectural elements. The complex covers an extensive area with varying elevations.

Location & Access Logistics

The Citadel is located approximately 2.5 kilometers south of Cairo's city center. Access is typically via Salah Salem Road. Driving is the most common method, with parking available within the Citadel complex, though capacity can be limited during peak hours. Public transport options include bus routes that stop near the Citadel's base, requiring a short uphill walk or a taxi ride to the entrance. Metro Line 1 stops at Attaba station, from which a taxi or bus is necessary.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Construction began in 1176 CE under Saladin to defend Cairo and Fustat from potential Crusader attacks. It served as the seat of government for Egypt for nearly 700 years, housing sultans and rulers of the Ayyubid, Mamluk, and Ottoman dynasties, as well as the Muhammad Ali dynasty. The Citadel is built on a natural elevation of the Mokattam Hills, a geological formation of limestone.

Key Highlights & Activities

Exploration of the various mosques, including the Mosque of Muhammad Ali Pasha and the Al-Nasir Muhammad Mosque. Viewing the panoramic cityscapes of Cairo from the ramparts. Visiting the various museums within the complex, such as the National Military Museum and the Carriage Museum. Observing the architectural details of different historical periods.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available within the complex. Limited shaded areas are present, primarily around the mosques and within museum buildings. Cell phone signal (4G/5G) is generally available. Food vendors and small cafes are located within the Citadel grounds, offering refreshments and light meals.

Best Time to Visit

The best time of day for photography is late afternoon, approximately 1-2 hours before sunset, for optimal lighting on the structures and city views. The most favorable months for visiting are from October to April, avoiding the intense summer heat. High tide is not a relevant factor for this land-based landmark.

Facts & Legends

A notable historical oddity is the tomb of the Ottoman governor, Muhammad Bey Abu al-Dhahab, located within the complex. A "secret" tip for visitors is to explore the less-visited sections of the outer walls for different perspectives of the Citadel's scale and construction.

Nearby Landmarks

- Mosque of Ibn Tulun (1.5km West)

- Al-Azhar Mosque (2.0km Northwest)

- Khan el-Khalili Bazaar (2.2km Northwest)

- Sultan Hassan Mosque and Al-Rifa'i Mosque (2.8km West)

- Egyptian Museum (3.5km West)