Information

Landmark: Elfreth’s AlleyCity: Philadelphia

Country: USA Pennsylvania

Continent: North America

Elfreth’s Alley, Philadelphia, USA Pennsylvania, North America

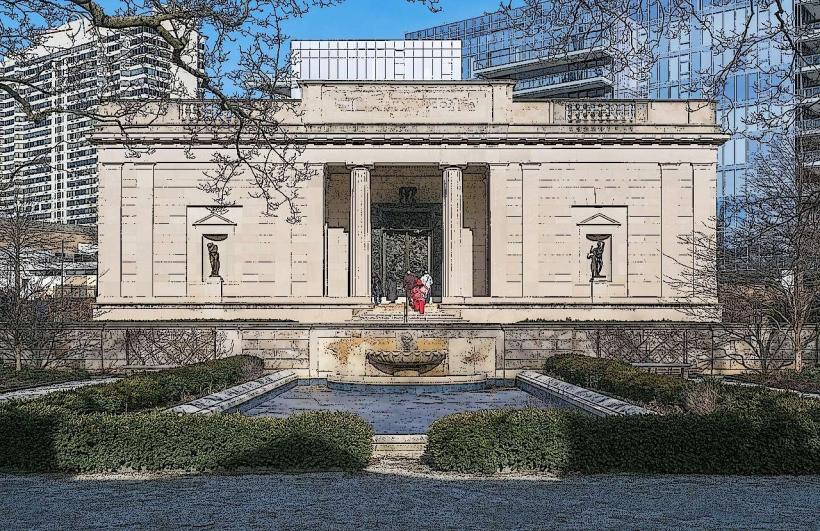

Elfreth’s Alley is a historic residential street located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

It is recognized as the oldest continuously inhabited residential street in the United States.

Visual Characteristics

The alley consists of 32 brick row houses constructed between the early 18th century and the mid-19th century. The buildings are primarily two-and-a-half stories high, featuring varied brickwork patterns, including Flemish bond and common bond. Architectural styles range from Georgian to Federal. Window styles include sash windows and some dormer windows. The street surface is paved with cobblestones.

Location & Access Logistics

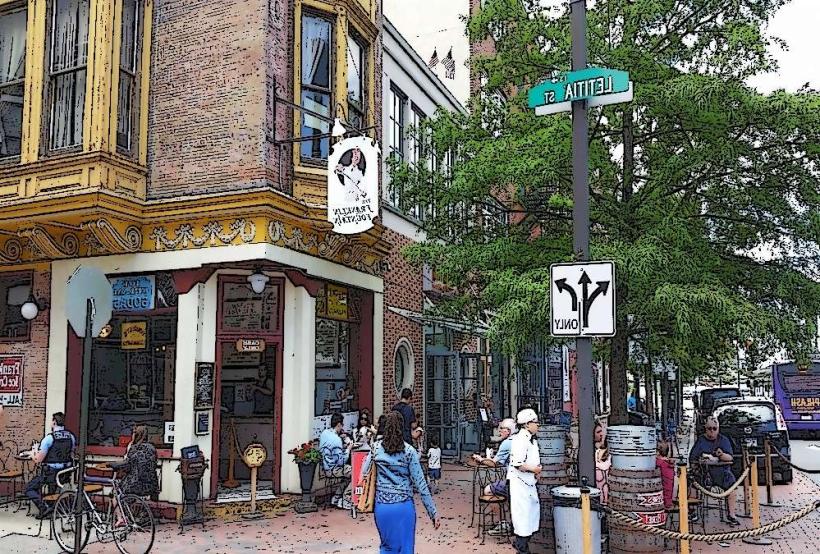

Elfreth’s Alley is situated in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia. It is located between Front Street and 2nd Street, running from Arch Street to Race Street. The alley is approximately 0.5km East of Independence Hall. Parking in the immediate vicinity is limited to metered street parking on surrounding streets. Public transport options include SEPTA bus routes 5, 17, 21, 42, and 47, which stop within a 0.2km radius. The nearest subway station is 5th Street Station (Market-Frankford Line), approximately 0.4km West.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Elfreth’s Alley was developed between approximately 1703 and 1836. It originated as a service lane for artisans and tradespeople who lived and worked in the area. The street was named after Jeremiah Elfreth, a blacksmith and property owner who lived on the street in the late 18th century. The original purpose was to provide housing and access for the working class in Philadelphia's early commercial district.

Key Highlights & Activities

Visitors can walk the length of the alley, observing the historic architecture. Several houses are open as museums, including the Elfreth’s Alley Museum (House #126), which offers guided tours detailing the lives of past residents. Photography of the streetscape is permitted. Special events, such as Fete Day, occur annually.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available at the Elfreth’s Alley Museum. Limited shade is provided by the buildings themselves. Cell phone signal (4G/5G) is generally available. Food vendors and restaurants are located on the adjacent commercial streets, such as 2nd Street.

Best Time to Visit

For optimal lighting for photography, early morning or late afternoon is recommended. The best months for visiting are April through October, offering milder weather. There are no tide-dependent activities associated with Elfreth's Alley.

Facts & Legends

A notable historical fact is that Elfreth's Alley was nearly demolished in the 1930s to make way for a parking lot. A preservation campaign led by residents successfully saved the street. A local legend suggests that some of the original residents' spirits still inhabit the alley.

Nearby Landmarks

- Museum of the American Revolution (0.3km West)

- Betsy Ross House (0.2km Northwest)

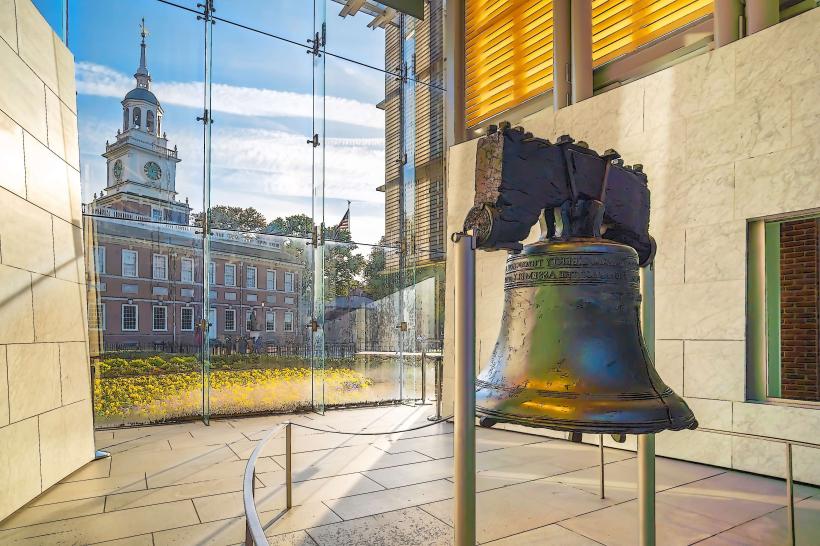

- Independence Hall (0.5km West)

- Christ Church (0.3km Southwest)

- Franklin Square (0.6km West)