Information

Landmark: Maroni RiverCity: Saint Laurent du Maroni

Country: French Guiana

Continent: South America

Maroni River, Saint Laurent du Maroni, French Guiana, South America

The Maroni River forms a significant portion of the border between French Guiana and Suriname. It is a major waterway in the Amazon basin.

Visual Characteristics

The Maroni River is characterized by its muddy brown water, a result of sediment carried from the interior. The riverbanks are densely vegetated with tropical rainforest, featuring a variety of tree species. The width of the river varies, but it can be several kilometers wide in certain sections. The riverbed is composed of sand and silt.

Location & Access Logistics

The Maroni River is accessible from Saint Laurent du Maroni, French Guiana. The city is located on the eastern bank of the river. Access to the river itself is primarily via boat. Local boat operators offer transport services from the Saint Laurent du Maroni port. Road access to Saint Laurent du Maroni is via Route Nationale 1 (RN1). Parking is available in designated areas within Saint Laurent du Maroni, near the port facilities. Public transport within Saint Laurent du Maroni is limited to local taxis.

Historical & Ecological Origin

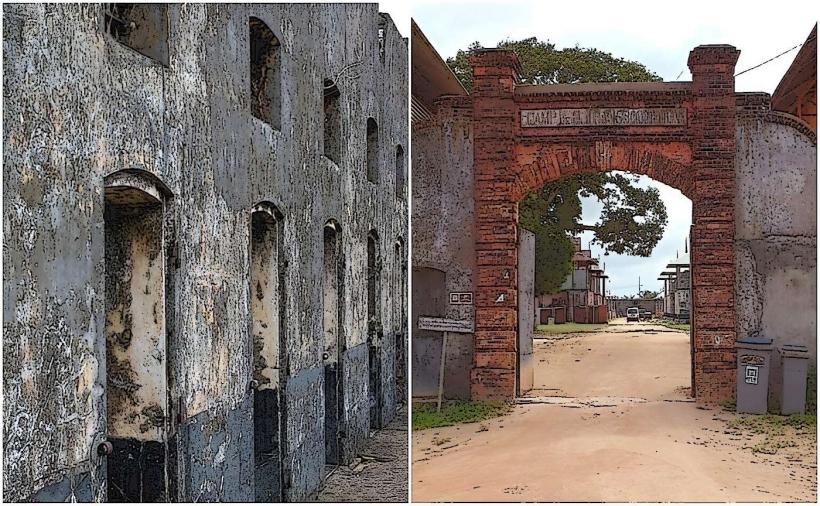

The Maroni River is a natural waterway, part of the larger Amazon drainage basin. Its formation is a result of geological processes over millions of years, carving its path through the Guiana Shield. Historically, the river served as a vital transportation route for indigenous populations and later for colonial powers. It was also a significant route for the penal colony established in Saint Laurent du Maroni.

Key Highlights & Activities

Boat excursions along the Maroni River are the primary activity. These trips can include visits to the former penal colony of Île Royale and Île Saint-Laurent. Observing the diverse riverine flora and fauna is possible. Fishing is also practiced by local communities.

Infrastructure & Amenities

In Saint Laurent du Maroni, near the port, basic amenities such as restrooms are available. Food vendors are often present in the vicinity of the port. Cell phone signal (4G) is generally available in Saint Laurent du Maroni. Shade is limited along the riverbanks themselves, but available on boats and in the town.

Best Time to Visit

The dry season, from July to December, offers more predictable weather for river excursions. The best time of day for photography is generally in the morning or late afternoon when the light is less harsh. High tide is not a significant factor for most river travel, but water levels can fluctuate seasonally.

Facts & Legends

The Maroni River was historically known as the "Devil's River" by some early explorers due to its challenging currents and dense, often impenetrable, surrounding jungle. The river's ecosystem supports a variety of fish species, including piranha and various catfish.

Nearby Landmarks

- Former Penal Colony of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni (0.2km West)

- Île Royale (5km Northwest)

- Maripasoula (75km Southwest)

- Cacao Village (40km East)