Information

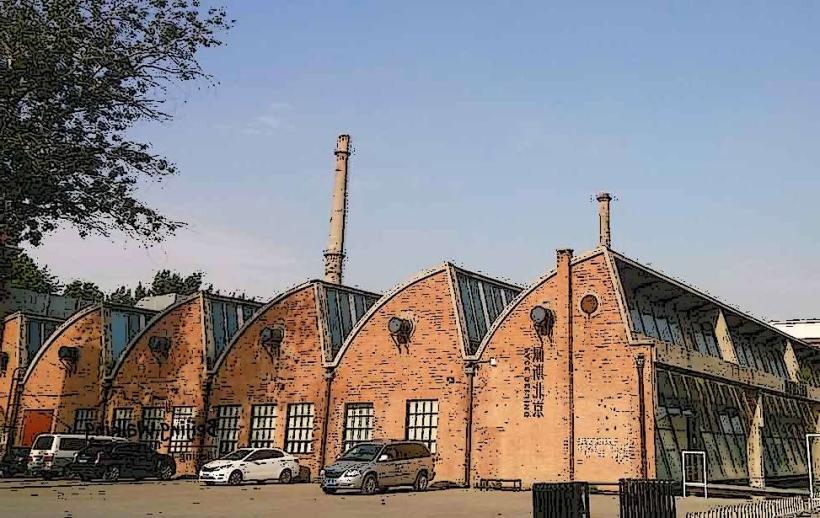

Landmark: Peking OperaCity: Beijing

Country: China

Continent: Asia

Peking Opera, Beijing, China, Asia

Peking Opera is a traditional Chinese performing art form originating in Beijing, China. It combines music, vocal performance, mime, dance, and acrobatics.

Visual Characteristics

Performers wear elaborate costumes made of silk and embroidery, often featuring bright colors and intricate patterns. Facial makeup is highly symbolic, with specific colors and designs indicating character traits. The stage is typically a simple, rectangular platform, often with a backdrop depicting traditional Chinese motifs. Performances are accompanied by a distinct orchestra featuring traditional Chinese instruments such as the jinghu (a two-stringed fiddle), yueqin (moon-shaped lute), and various percussion instruments.

Location & Access Logistics

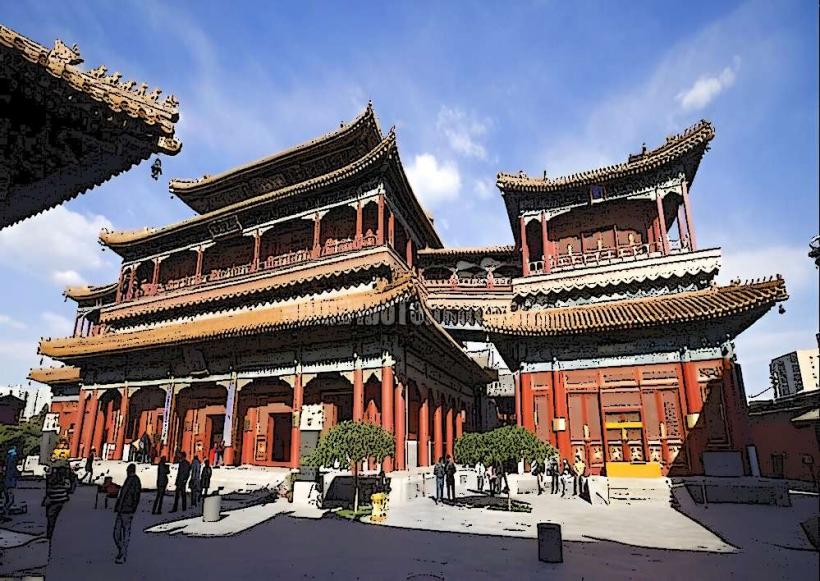

Peking Opera performances are primarily held in dedicated theaters within Beijing. Major venues include the Lao She Teahouse (located at 7 Qianmen Street, Dongcheng District) and the Mei Lanfang Grand Theater (located at 33 West Chang'an Avenue, Xicheng District). Access is via Beijing Subway Lines 1, 2, or 4, with stations like Qianmen or Xidan being common disembarkation points. Taxis are readily available throughout the city.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Peking Opera emerged in the late 18th century, evolving from various regional opera forms. The Anhui Troupe is credited with bringing its style to Beijing in 1790, leading to the development of what is now known as Peking Opera. It was officially recognized as a distinct art form in the mid-19th century and became a significant cultural element during the Qing Dynasty.

Key Highlights & Activities

Attend a full-length opera performance, which can last several hours. Shorter excerpts or single acts are often available for visitors with limited time. Observe the detailed costume changes and the symbolic facial makeup application. Participate in pre-performance talks or workshops offered at some venues to understand the cultural context and performance techniques.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Major Peking Opera venues typically offer seating, restrooms, and sometimes on-site food and beverage services. Cell phone signal (4G/5G) is generally available within the theaters. Some venues may have gift shops selling opera-related merchandise.

Best Time to Visit

Performances are scheduled year-round. Evening performances are most common, typically starting between 7:00 PM and 7:30 PM. For optimal viewing of the performers' expressions and costumes, seating in the mid-range sections of the theater is recommended. Booking tickets in advance is advisable, especially for popular performances or during national holidays.

Facts & Legends

The distinctive facial makeup, known as lianpu, uses color to convey character traits: red signifies loyalty and bravery, white indicates treachery, and black represents impartiality. A specific legend tells of the actor Mei Lanfang, a master of female roles, who was so convincing that audiences often forgot he was a man.

Nearby Landmarks

- Tiananmen Square: 1.2km North

- Forbidden City: 1.5km North

- National Museum of China: 1.3km Northeast

- Temple of Heaven Park: 4.5km South

- Wangfujing Street: 2.0km East