Information

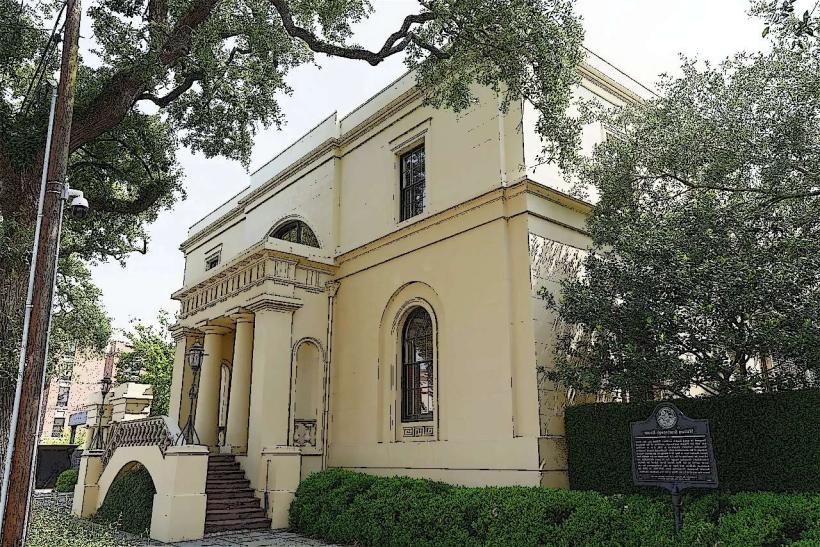

Landmark: Owens-Thomas HouseCity: Savannah

Country: USA Georgia

Continent: North America

Owens-Thomas House, Savannah, USA Georgia, North America

The Owens-Thomas House is a historic house museum located in Savannah, Georgia, USA.

It is a significant example of Regency architecture and a preserved urban mansion.

Visual Characteristics

The house is constructed of brick with stucco facing. It features a symmetrical facade with a central portico supported by four Doric columns. The exterior color is a pale yellow. The building stands three stories high, with a basement level. Architectural style is Regency, characterized by classical proportions and decorative elements.

Location & Access Logistics

The Owens-Thomas House is situated at 124 Abercorn Street, Savannah, GA 31401. It is located in the heart of Savannah's historic district, approximately 0.5km South of the Savannah River. On-street parking is available in the surrounding blocks, though metered and often limited. Public transport options include the Chatham Area Transit (CAT) bus system; Route 14 stops within a 2-minute walk at the intersection of Abercorn Street and Oglethorpe Avenue.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Construction of the Owens-Thomas House began in 1816 and was completed in 1819. It was designed by William Jay, an English architect. The original purpose was to serve as a private residence for the wealthy merchant Richard Richardson. It later became the home of George Owens and then Francis M. Torrey. The site itself is part of Savannah's original city plan, laid out by James Oglethorpe.

Key Highlights & Activities

Visitors can participate in guided tours of the house, which cover the main residence, the restored urban slave quarters, and the carriage house. Photography is permitted in designated areas. The house museum offers insights into the lives of both the owners and the enslaved people who lived and worked there.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available on-site for visitors. Shaded areas are present within the house's interior and in the courtyard. Cell phone signal (4G/5G) is generally reliable within the museum. Food vendors and restaurants are located within a 5-minute walk in the surrounding historic district.

Best Time to Visit

The best time of day for interior photography is mid-morning, between 10:00 AM and 12:00 PM, when natural light enters through the windows. The best months for visiting are April, May, September, and October, offering mild temperatures. No specific tide requirements apply to this inland landmark.

Facts & Legends

A notable historical oddity is the presence of a rare intact urban slave quarters, providing a direct comparison to the main house and offering a more complete picture of 19th-century domestic life. The house also features a unique "ice house" in the basement, an early form of refrigeration.

Nearby Landmarks

- Telfair Academy (0.2km West)

- Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace (0.3km South)

- Colonial Park Cemetery (0.4km North)

- Cathedral of St. John the Baptist (0.6km Southwest)

- Forsyth Park (1.2km South)