Information

City: PotosiCountry: Bolivia

Continent: South America

Potosi, Bolivia, South America

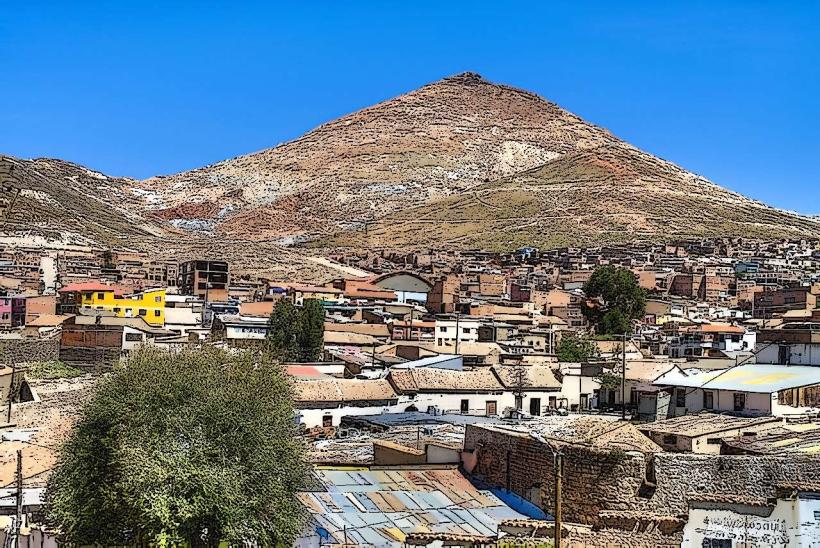

Potosí serves as the capital of the Potosí Department and remains one of the highest cities in the world, situated at an elevation of 4,090m. It is dominated by the Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain), which once provided the vast majority of the silver used by the Spanish Empire.

Historical Timeline

The city was founded in 1545 following the discovery of silver ore. By the early 17th century, it was one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the world, with a population exceeding 160,000. Its governance transitioned from a colonial economic powerhouse to a republican mining center. The most significant historical event was the 1987 designation of the city as a UNESCO World Heritage site, though it was placed on the "List of World Heritage in Danger" in 2014 due to the potential collapse of the Cerro Rico from centuries of uncontrolled mining.

Demographics & Population

The estimated 2026 population is 215,000. The demographic profile is predominantly indigenous Quechua and Mestizo. The median age is approximately 23 years, with a high percentage of the workforce employed in the mining and informal sectors.

Urban Layout & Key Districts

The city is built on a steep slope, with narrow, winding streets typical of Andean colonial planning.

Casco Histórico: The central zone containing the most significant colonial architecture and the Mint.

Barrio Minero: The higher-elevation districts near the base of Cerro Rico, where most mining families reside.

The Low Zone: Newer residential expansions at slightly lower elevations with more modern infrastructure.

Top City Landmarks

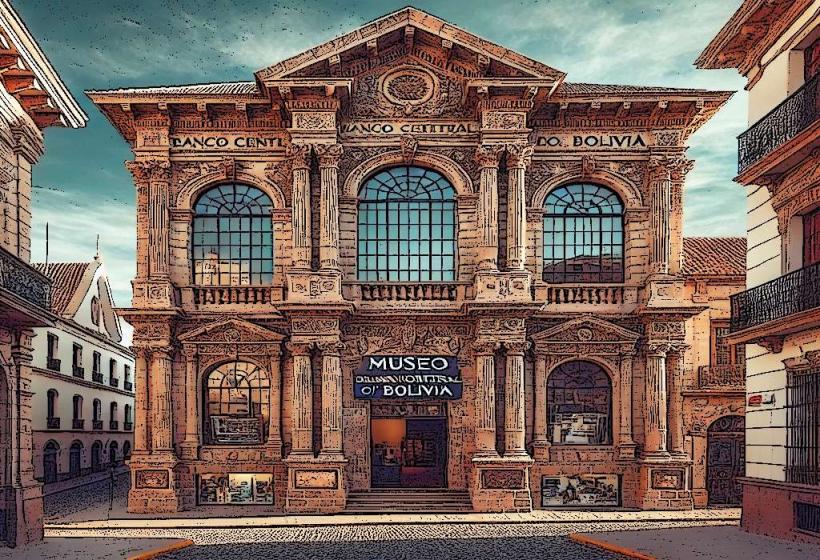

Casa Nacional de la Moneda: A massive colonial mint and museum considered the most important historical building in Bolivia.

Cerro Rico: The mountain overlooking the city, which can be visited via guided mine tours.

Convent of Santa Teresa: A restored colonial convent known for its religious art and architecture.

San Lorenzo de Carangas Church: Renowned for its intricate "Baroque-Mestizo" stone-carved facade.

Plaza 10 de Noviembre: The central square surrounded by the cathedral and municipal palace.

Transportation Network

Potosí lacks a mass transit system. Transit is provided by "micros" and shared "trufis." Capitán Nicolás Rojas Airport (POI) has limited service; most travelers arrive via bus from Sucre (3 hours) or Uyuni (4 hours). Traffic is highly congested in the narrow colonial core. Pedestrian movement is physically demanding due to the extreme altitude and steep inclines.

Safety & "Red Zones"

Potosí is relatively safe regarding violent crime, but petty theft occurs in markets.

Red Zones: The areas immediately surrounding the mining shafts at night should be avoided.

Industrial Risks: Mine tours involve significant risks, including exposure to silica dust, noxious gases, and structural instability.

Protests: The department is known for frequent and aggressive "paros cívicos" (strikes) that can block all transit into and out of the city.

Digital & Financial Infrastructure

Average internet speed is 20-40 Mbps. Fiber optic is available but less widespread than in Sucre. Main carriers are Entel and Tigo. The city is heavily cash-reliant; while cards are accepted in major hotels and the main museum, local commerce and tours require Bolivianos. ATMs are concentrated near the main plaza.

Climate & Health Risk

The climate is cold and semi-arid. Temperatures frequently drop below 0°C at night, especially from June to August. Altitude Sickness is a severe risk; physical exertion is difficult even for those acclimated to Sucre. Air quality is affected by mineral dust and old vehicle emissions.

Culture & Social Norms

Mining Culture: The city’s identity is inextricably linked to the mines and the "Tío" (the deity of the underworld to whom miners offer coca leaves, alcohol, and cigarettes).

Tipping: 10% is appreciated but not mandatory.

Dress: Heavy, layered clothing is essential year-round.

Accommodation Zones

Historic Center: Recommended for proximity to the Mint and colonial churches.

Lower City: Recommended for slightly more modern hotel facilities.

Local Cost Index

1 Espresso: 12 BOB ($1.75 USD)

1 Standard Lunch: 25 BOB ($3.60 USD)

1 Mine Tour: 150–200 BOB ($21.00–$29.00 USD)

Nearby Day Trips

Tarapaya (Ojo del Inca): 25 km (Natural thermal volcanic lagoon).

Cayara: 20 km (A historic colonial hacienda and museum).

Uyuni: 200 km (Gateway to the Salt Flats, typically a 4-hour bus ride).

Facts & Legends

A famous legend states that the Spanish could have built a silver bridge from Potosí to Madrid with the ore extracted, and a bridge of bones with the lives of the millions of indigenous people and African slaves who died in the mines. Historically, the Potosí mint mark (a superimposed "PTSI") is widely considered the origin of the modern dollar ($) symbol.