Information

Landmark: Bougainville Copper MineCity: Provice Area

Country: Papua New Guinea

Continent: Australia

Bougainville Copper Mine, Provice Area, Papua New Guinea, Australia

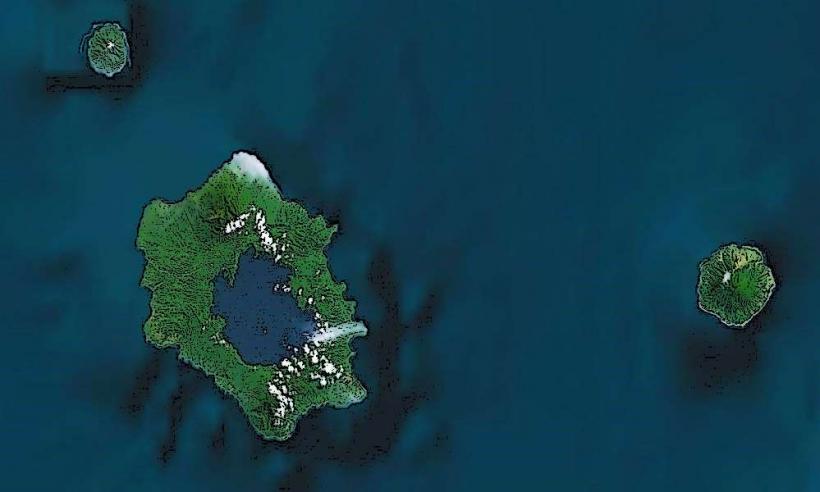

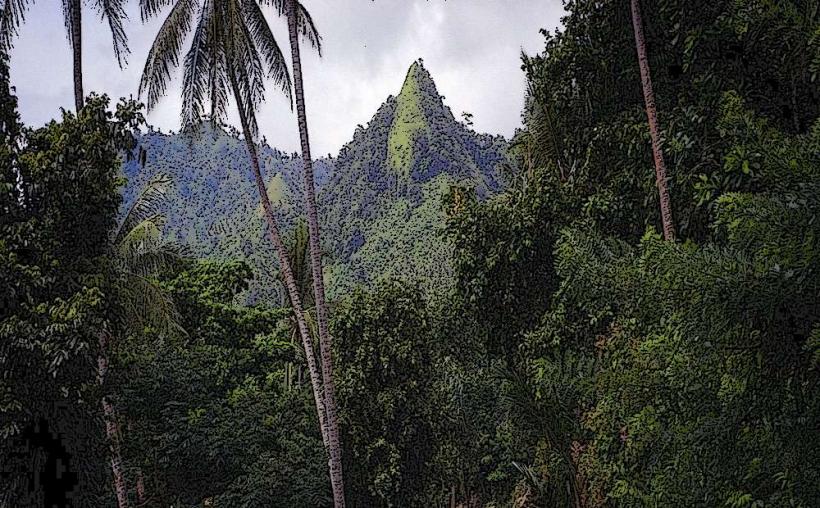

The Bougainville Copper Mine is a large-scale open-pit copper and gold mine located on the island of Bougainville in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea.

This site is characterized by its immense scale, featuring a vast open pit that measures approximately 3.5 kilometers in diameter and 1.2 kilometers in depth. The exposed rock faces reveal stratified layers of mineralized ore, primarily copper sulfides and gold-bearing quartz. The surrounding landscape is heavily impacted by mining operations, with extensive tailings dams and processing facilities.

Location & Access Logistics

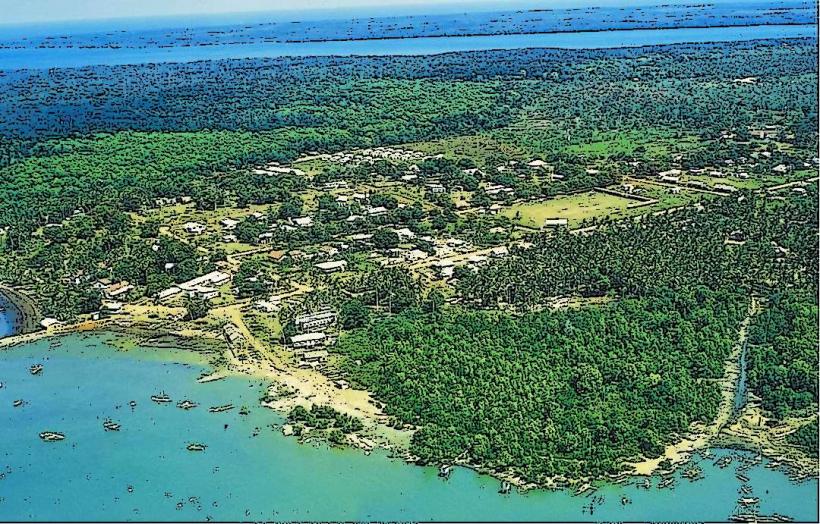

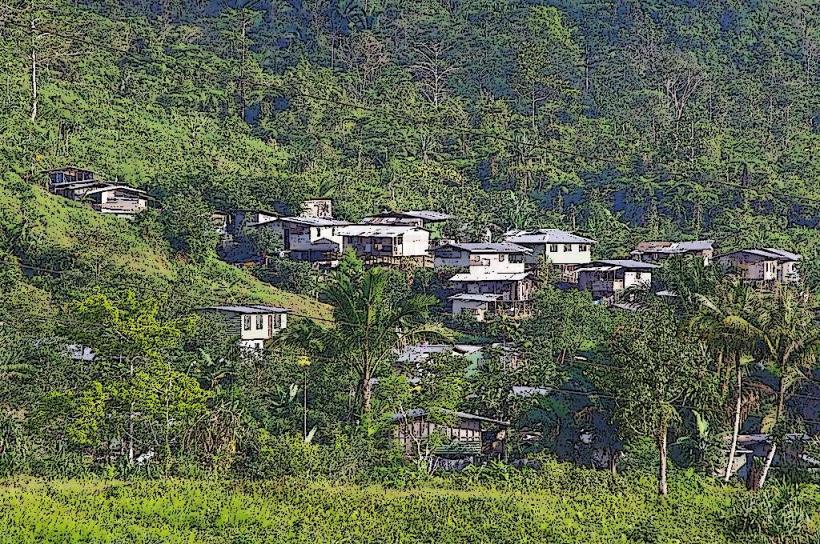

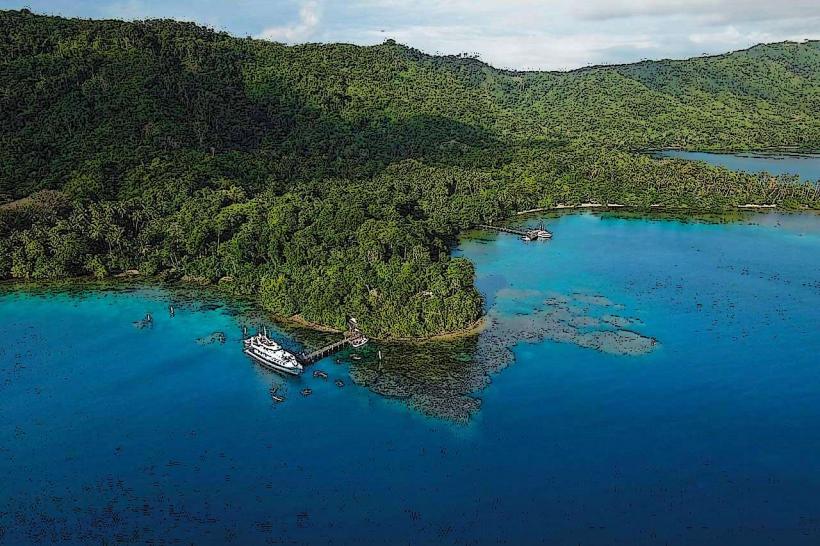

The mine is situated inland from the coastal town of Panguna. Access is primarily via unpaved roads originating from Panguna. Historically, a dedicated road network served the mine, but its current condition is subject to ongoing maintenance and security considerations. Due to its remote location and past operational status, public access is restricted and requires specific permits and arrangements. There are no regular public transport services directly to the mine site.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Exploration and development of the Bougainville Copper Mine began in the 1960s, with commercial production commencing in 1972. The mine was operated by Bougainville Copper Limited (BCL), a joint venture involving Rio Tinto. Its original purpose was the extraction of significant copper and gold deposits. The geological formation is part of the Porphyry Copper Deposit type, associated with a Tertiary volcanic arc.

Key Highlights & Activities

Due to its operational status and environmental considerations, direct visitor activities at the mine site are not generally permitted. The primary "activity" is observation of the scale of the open pit and associated infrastructure from designated safe viewing points, if accessible. Historical tours focusing on the mine's operational past may be arranged through specific local authorities or historical societies, subject to availability and safety protocols.

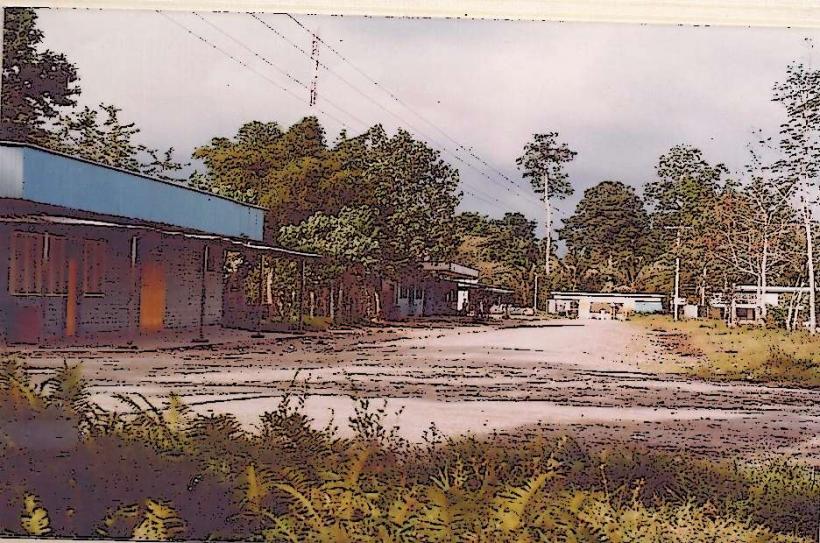

Infrastructure & Amenities

The mine site historically possessed extensive infrastructure including processing plants, power generation facilities, and accommodation for workers. However, much of this infrastructure is now disused or in a state of disrepair. Basic amenities such as restrooms and food vendors are not available at the mine site itself. Cell phone signal is unreliable and generally absent within the immediate vicinity of the pit.

Best Time to Visit

The best time for any potential site visit, if permitted, would be during the dry season, typically from June to September, to minimize travel disruptions caused by heavy rainfall. Lighting conditions for photography would be most favorable during early morning or late afternoon, avoiding the harsh midday sun which can reduce detail in the exposed rock faces.

Facts & Legends

The Bougainville Copper Mine was once one of the world's largest and most profitable copper mines. A significant historical oddity is the prolonged closure of the mine in 1989 due to an armed conflict, which had a profound impact on the region's economy and environment. Local legends often speak of the immense wealth extracted from the earth and the subsequent environmental changes.

Nearby Landmarks

- Panguna Town (0.8km West)

- Mount Balbi (15km North-West)

- Kieta Port (25km East)