Information

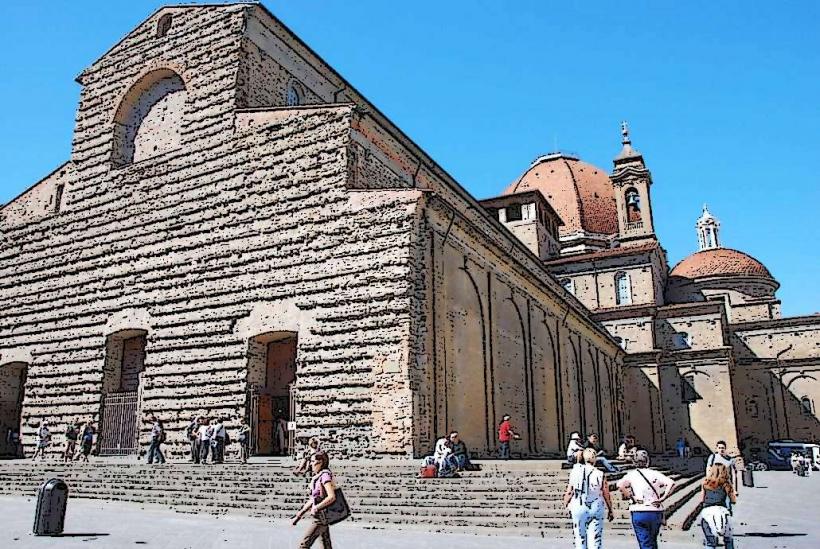

Landmark: Cappella BrancacciCity: Florence

Country: Italy

Continent: Europe

Cappella Brancacci, Florence, Italy, Europe

The Brancacci Chapel is a small chapel located within the Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine in the Oltrarno district of Florence. It is known as the "Sistine Chapel of the Early Renaissance" due to its influential fresco cycle.

Visual Characteristics

The chapel is situated in the south transept of the church. The walls are covered in two horizontal tiers of frescoes depicting the Life of Saint Peter. The style marks the transition from Gothic to Renaissance, utilizing early linear perspective, consistent lighting from a single source, and deep emotional realism in the figures. The colors are dominated by earth tones and lapis lazuli blues.

Location & Access Logistics

The chapel is located at Piazza del Carmine. Entry is not through the main church facade but through a separate door in the cloister (Piazza del Carmine 14). It is a 15-minute walk (1.2km) from the Firenze Santa Maria Novella railway station. Due to the delicate nature of the frescoes, entry is strictly limited to small groups (approx. 30 people) for 15-minute intervals. Reservations are mandatory.

Historical & Ecological Origin

Commissioned around 1424 by Felice Brancacci, a wealthy silk merchant. The frescoes were begun by Masolino da Panicale and his pupil Masaccio. Work stopped in 1428 when Masaccio died in Rome and Brancacci was exiled. The cycle remained unfinished for over 50 years until completed by Filippino Lippi in the 1480s. The chapel survived a catastrophic fire in 1771 that destroyed most of the surrounding basilica.

Key Highlights & Activities

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (Masaccio): Notable for the intense psychological distress shown in Adam and Eve’s faces.

The Tribute Money (Masaccio): Demonstrates the revolutionary use of atmospheric perspective and shadows.

St. Peter Preaching (Masolino): Shows the softer, more traditional Gothic influence for comparison.

Archaeological Scaffolding: Periodically, "open-site" tours allow visitors to climb scaffolding for a close-up view of the brushwork during restoration phases.

Infrastructure & Amenities

The site includes a multimedia room with a video introduction to the frescoes, a small bookshop, and accessible restrooms. Cellular signal is functional in the cloister but weak inside the chapel. The space is climate-controlled to preserve the plaster; photography is permitted without flash.

Best Time to Visit

Reservations should be made at least 2–3 weeks in advance. The earliest morning slots (09:00–10:00) offer the quietest experience. The chapel is closed on Tuesdays. Because the viewing time is strictly 15 minutes, visitors should utilize the multimedia room before entry to understand the narrative layout.

Facts & Legends

The chapel served as a "school for the world"; Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael all studied Masaccio’s techniques here. A historical legend claims that Michelangelo’s nose was broken in this very chapel during an argument with fellow sculptor Pietro Torrigiano over the quality of their respective drawings of the frescoes.

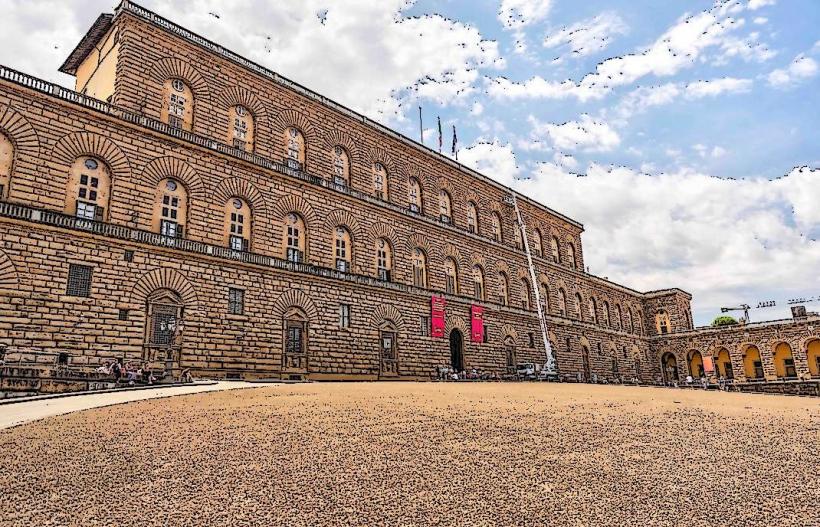

Nearby Landmarks

Piazza Santo Spirito: 0.4km East

Palazzo Pitti: 0.8km Southeast

Ponte Vecchio: 1.0km East

Basilica di Santa Maria del Carmine: 0km (Houses the chapel)

Piazza della Signoria: 1.2km Northeast