Information

Landmark: Chiesa di San Gottardo in CorteCity: Milan

Country: Italy

Continent: Europe

Chiesa di San Gottardo in Corte, Milan, Italy, Europe

Chiesa di San Gottardo in Corte is one of Milan’s most historically resonant and architecturally intriguing churches-a compact yet refined sanctuary built within the shadow of power. Hidden just behind Palazzo Reale, near Piazza del Duomo, it was originally conceived as the private chapel of the Visconti court, combining spiritual devotion with the grandeur of Milan’s early Gothic period.

Origins and Foundation

The church was commissioned in 1330 by Azzone Visconti, the Lord of Milan, who dedicated it to Saint Gotthard of Hildesheim, patron saint of the sick, in gratitude for his recovery from illness. At that time, Milan was transforming from a medieval commune into the stronghold of the Visconti dynasty-a city that blended piety with political ambition.

San Gottardo in Corte was designed by Francesco Pecorari of Cremona, one of the early proponents of Gothic architecture in Lombardy. Unlike the monumental Gothic of the later Duomo, San Gottardo’s proportions are intimate and measured, reflecting its function as a ducal chapel rather than a public basilica. It formed part of the larger Visconti Palace complex, hence the name in Corte-“in the court.”

Architecture and Design

The church represents a transitional moment between the Romanesque and Gothic styles. Its structure features pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and slender columns, yet retains a grounded simplicity that feels more Lombard than French. The brick exterior, discreet and harmonious, contrasts with the vertical thrust of the octagonal bell tower, which soon became a landmark of the medieval city.

That tower, completed in 1336, holds a special place in Milan’s history-it contained the first public clock in the city. This innovation, unprecedented for the time, allowed citizens to regulate their day by a common standard, symbolizing Milan’s emerging sense of civic order.

The façade visible today is not original; it was redesigned in the 18th century by Giuseppe Perego, who softened its Gothic character with Baroque touches-rounded pediments, stucco reliefs, and balanced ornamentation that lend the building a refined, courtly grace.

Interior and Artistic Treasures

Inside, the church unfolds as a serene interplay of light and shadow, where centuries of artistic intervention coexist. The single nave is modest in scale but rich in detail, its walls covered with frescoes and stucco decoration that reflect the layered history of Milanese art.

The main apse preserves one of the most valuable frescoes of the 14th century: a Crucifixion attributed to Giovanni da Milano, a pupil of Giotto. Its delicate faces, draped garments, and soft modeling of light represent an early step toward Renaissance naturalism. Nearby, fragments of frescoes depicting prophets and angels hint at the church’s original Gothic program.

The vaulted ceiling was later enriched with Baroque paintings, their gilded frames catching the dim light that filters through the small stained-glass windows. These decorations, combined with the stone ribbing and wooden choir stalls, create a visual rhythm that draws the visitor’s gaze upward without overwhelming the eye.

Several side altars display works by later Lombard artists, including Renaissance and Counter-Reformation paintings of saints, Madonna scenes, and moments from Christ’s Passion. These altars, installed between the 16th and 17th centuries, reflect the church’s adaptation to new devotional needs while maintaining its intimate character.

The Bell Tower and the First Public Clock

The bell tower of San Gottardo in Corte stands as one of the most important civic symbols of medieval Milan. Built shortly after the church’s completion, its octagonal structure rises in elegant tiers of brick and stone, with delicate Gothic openings that allow the sound of the bells to carry across the old city.

In 1336, Azzone Visconti ordered the installation of Milan’s first mechanical clock, a technological marvel of its age. It marked not only the hours of prayer but also the rhythm of civic life-markets, workshops, and public offices began to follow the bell’s chime. This innovation effectively made San Gottardo the timekeeper of Milan, a role that underscores the union of faith and governance in the Visconti era.

Connection to Palazzo Reale

Originally, the church was physically connected to the Visconti ducal palace, which occupied much of the area where the Palazzo Reale stands today. A covered passage once linked the palace directly to the church, allowing the rulers to attend mass privately without entering the public square.

Although that passage has long disappeared, the church still stands as a spiritual echo of the old court, its side facing the palace’s inner courtyard. This proximity gives San Gottardo a dual identity-both sacred space and architectural extension of power.

When the Visconti dynasty ended, the palace and church continued to evolve under successive rulers, from the Sforza family to the Spanish and Austrian governors, and eventually the Italian monarchy. Throughout these transitions, San Gottardo remained a place of worship and ceremony tied to Milan’s civic authority.

Restoration and Modern Role

The church suffered periods of neglect, particularly after the ducal court moved and the palace lost prominence. It underwent major restorations in the 19th and 20th centuries, including work after World War II damage, which aimed to recover its medieval structure and preserve surviving frescoes.

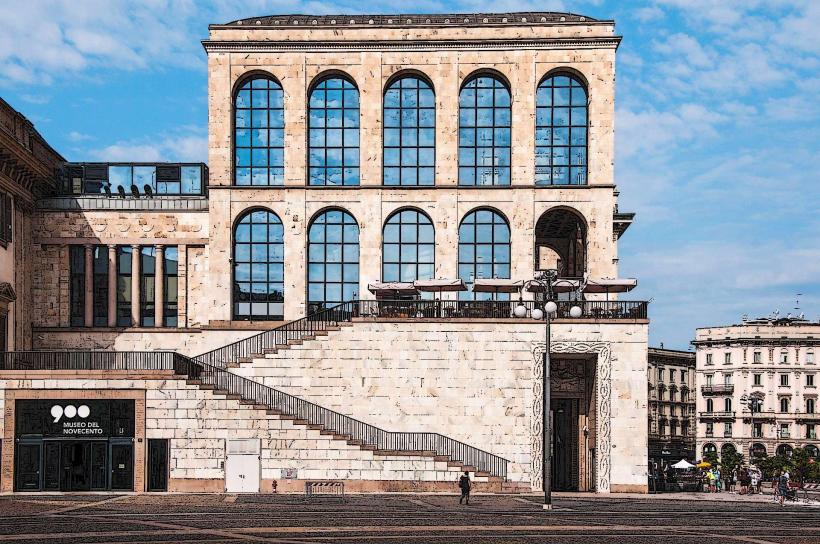

Today, San Gottardo in Corte is managed by the Museo del Duomo, which oversees its conservation and occasional use for exhibitions, concerts, and guided visits. Though no longer a parish church, it remains an active space for art, music, and reflection.

Atmosphere and Visitor Experience

Visiting San Gottardo in Corte feels like stepping into a fragment of Milan’s medieval soul preserved amidst the grandeur of the Duomo district. The air inside is cool and still, carrying a faint scent of wax and aged plaster. The hush is broken only by the creak of wooden pews or the distant murmur from the palace courtyard.

Unlike the vast Duomo nearby, this church speaks softly. Its proportions, frescoes, and muted colors invite contemplation rather than awe. The blend of Gothic bones and Baroque flesh creates a layered beauty-a building that has aged gracefully, adapting to each century while retaining its essence.

Standing beneath the bell tower, one can almost imagine the moment when Milan first heard the regular tolling of its new civic clock-a sound that once ordered the life of the entire city.

Legacy

The Chiesa di San Gottardo in Corte embodies Milan’s unique balance between faith, innovation, and political authority. Built as a ruler’s private chapel, it became a public monument of time, art, and devotion. It remains one of the city’s quiet treasures, often overlooked but deeply revealing of Milan’s character: elegant, disciplined, forward-looking, yet rooted in a centuries-old sense of purpose and grace.

Even today, in the heart of modern Milan, San Gottardo continues to mark the passage of time-not with the precision of its ancient clock, but with the enduring rhythm of history echoing through its walls.