Information

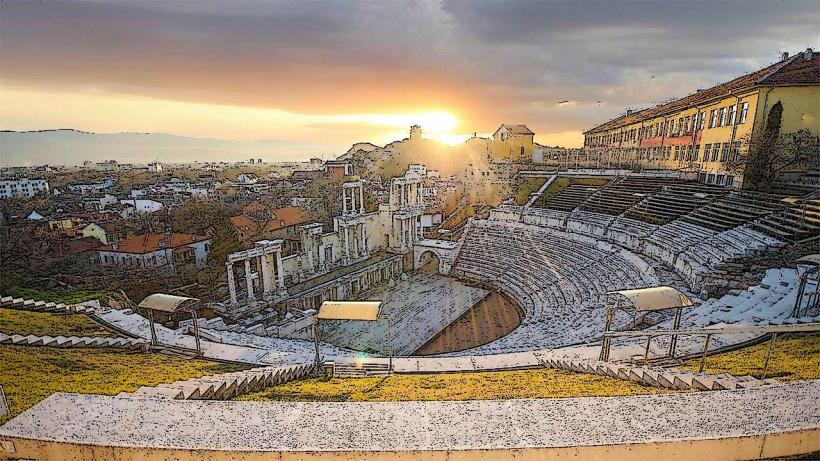

Landmark: Roman Fortress of DiocletianopolisCity: Plovdiv

Country: Bulgaria

Continent: Europe

Roman Fortress of Diocletianopolis, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, Europe

Diocletianopolis is a late Roman fortress located in the modern town of Hisarya within the Plovdiv Province. It was established as a major administrative and balneological center due to the presence of 22 mineral springs in the area.

Visual Characteristics

The fortress is defined by its massive fortification walls, which remain among the best-preserved Roman defenses in Europe, reaching heights of 11 meters. The walls are constructed using the opus mixtum technique, featuring alternating layers of processed stone and four rows of red bricks. The most prominent feature is "The Camels," a monumental southern gate characterized by a large arched passage and flanking towers.

Location & Access Logistics

The site is situated 42 kilometers north of Plovdiv and is accessible via Republican Road II-64. The town of Hisarya is a major stop on the railway line between Plovdiv and Karlovo. Bus services run hourly from Plovdiv's "South" bus station. Most of the ruins are located within the central "Lily of the Valley" park, which is a pedestrian-only zone with ample parking on its perimeter.

Historical & Ecological Origin

The fortress was founded in 293 AD by Emperor Diocletian on the site of an earlier Thracian settlement. It was built to protect the thermal springs and serve as a strategic garrison. Geologically, the area is part of the Sredna Gora mountain foothills, sitting atop a fault line that generates nitrogen-rich mineral waters with temperatures ranging from 37°C to 51°C.

Key Highlights & Activities

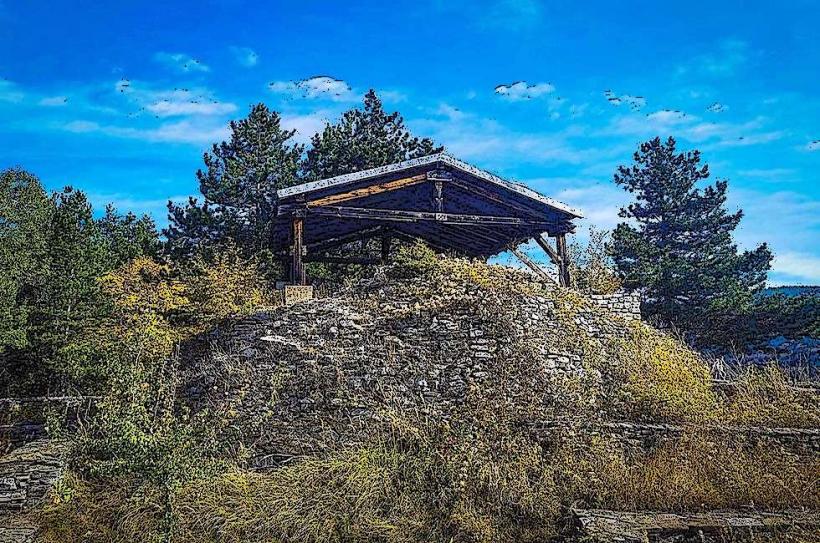

Visitors can walk the entire 2.3-kilometer perimeter of the fortification walls. Key excavated sites include the Roman baths, which feature original marble floors and drainage systems, and the late Roman residential complex. The archaeological museum houses a large collection of Roman glass and coin hoards found during excavations.

Infrastructure & Amenities

The archaeological reserve is integrated into the town's park system, featuring paved alleys, benches, and lighting. Public restrooms are located at the archaeological museum and near the southern gate. 5G cellular coverage is available throughout the site. Numerous cafes and specialized mineral water drinking fountains are scattered along the fortress walls.

Best Time to Visit

The best months for visiting are April through June or September through October to avoid high summer temperatures. Photography of "The Camels" gate is best in the late afternoon when the sun highlights the red brick layers. Spring is particularly suitable for viewing the ruins amidst the blooming park vegetation.

Facts & Legends

The southern gate earned the nickname "The Camels" in the early 20th century because the damaged central arch resembled two camels facing each other when viewed from a distance. A local legend suggests that the thermal water was so effective that Roman soldiers would recover from battle wounds twice as fast here than in any other part of the empire.

Nearby Landmarks

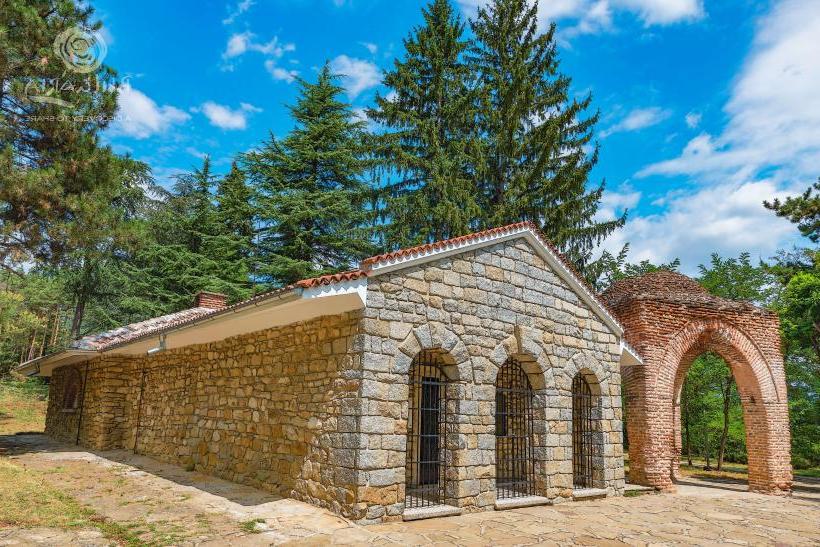

Hisarya Archaeological Museum – 0.2km West

Roman Family Tomb – 0.5km Southwest

Colonnade of the Mineral Spring "Momina Salza" – 0.3km North

St. Pantaleon Church – 0.4km East

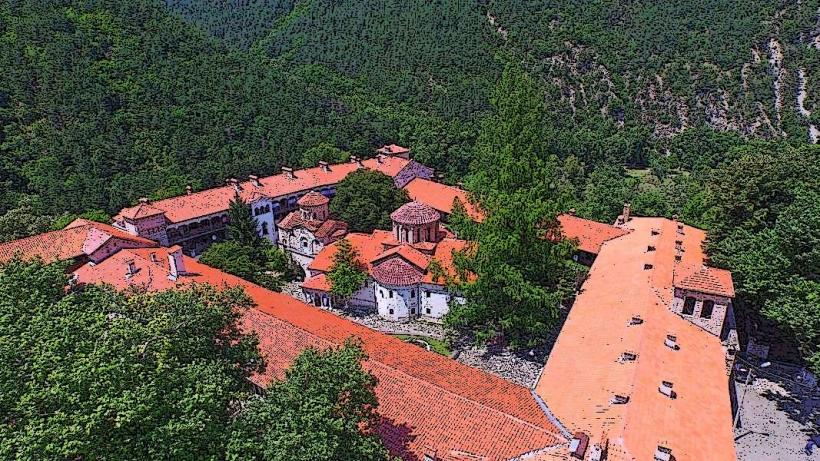

Thracian Cult Complex Starosel – 20.0km West