Information

Country: HaitiContinent: North America

Haiti, North America

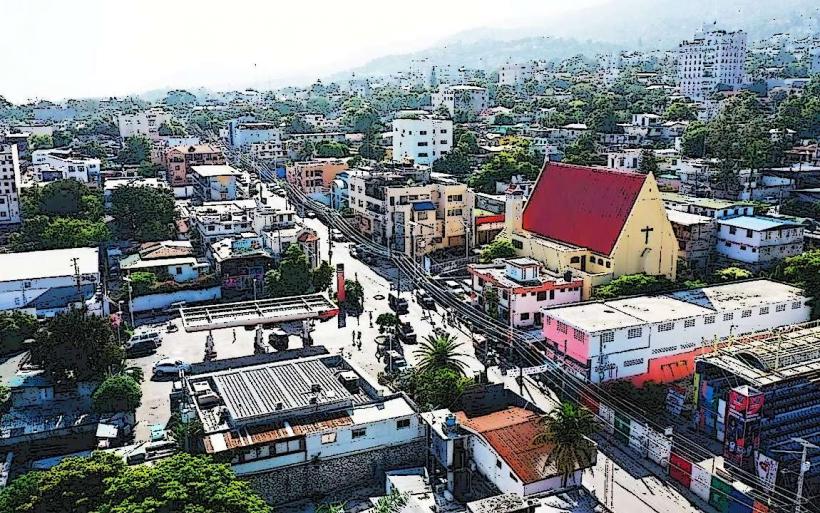

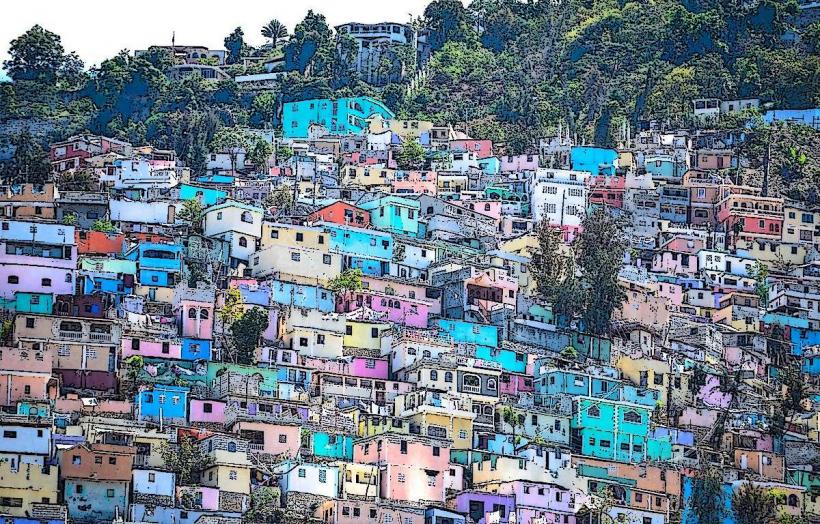

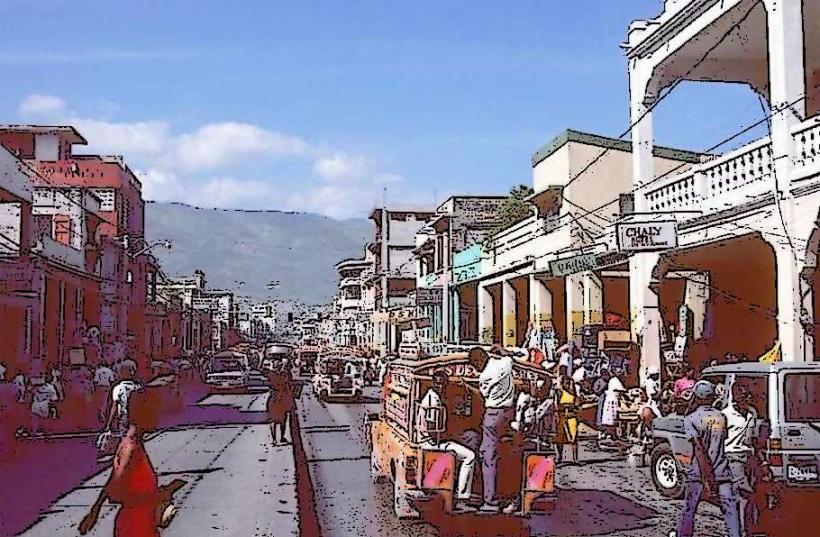

Haiti is located on the western third of the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles, bordering the Dominican Republic to the east. The country is defined by its mountainous terrain, which covers over 75% of its land area, and its history as the first independent nation in Latin America and the Caribbean; the capital city is Port-au-Prince.

Visa & Entry Policy

EU, US, and UK passport holders can enter Haiti visa-free for tourist stays of up to 90 days. Entry requires a passport valid for at least six months and a tourist fee of $10 USD payable in cash upon arrival at the airport. Travelers must also provide proof of a return ticket and accommodation; however, as of 2026, many foreign governments advise against all travel due to extreme civil unrest and the suspension of standard consular services.

Language & Communication

Haitian Creole (Kreyòl) and French are the official languages. Haitian Creole is the primary native tongue of nearly the entire population. English proficiency is low to medium, primarily limited to humanitarian workers, business professionals in the capital, and specific tourism sectors in the north. French remains the language of formal administration, legal proceedings, and secondary education.

Currency & Payment Systems

The official currency is the Haitian Gourde (HTG). While cards are accepted in high-end hotels and supermarkets in Pétion-Ville, cash is mandatory for the vast majority of transactions. Despite the official currency, many prices are quoted in "Haitian Dollars," a conceptual unit equal to 5 Gourdes. The US Dollar is widely accepted as a parallel currency for significant purchases. ATMs are present in urban centers but frequently suffer from cash shortages and technical failures.

National Transport Grid

Inter-city transport is dominated by "tap-taps," brightly painted shared buses or pickup trucks that operate on fixed routes with no set schedules. There is no rail network. Domestic aviation via Sunrise Airways connects Port-au-Prince to regional hubs like Cap-Haïtien, providing a vital alternative to road travel, which is frequently disrupted by gang-controlled checkpoints and security barricades.

Digital Infrastructure

The primary mobile network providers are Digicel and Natcom. 4G/LTE coverage is consistent in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area and major provincial towns, while 5G services have seen limited rollout in high-density commercial districts. Reliable internet access in the interior is scarce and often depends on satellite-based solutions.

Climate & Seasonality

The climate is tropical and semi-arid, with temperatures moderated by trade winds. Haiti experiences two rainy seasons: April to June and August to November. The country is highly vulnerable to hurricanes during the Atlantic season (June to November), and the southern peninsula is particularly prone to flash flooding and landslides due to extensive deforestation.

Health & Safety

No mandatory vaccines are required, but Hepatitis A, Typhoid, and Tetanus are strongly recommended. Malaria and Dengue are endemic nationwide, and cholera remains a persistent risk in areas with poor water sanitation. The national emergency number is 114 for the National Police and 116 for medical emergencies, though response times are unreliable.

Top 3 Major Regions & Cities

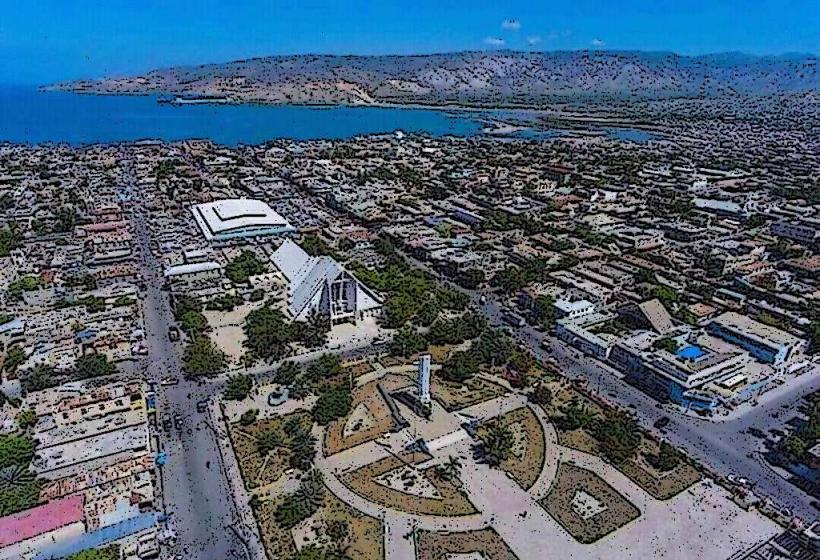

The Northern Coast: Hub: Cap-Haïtien.

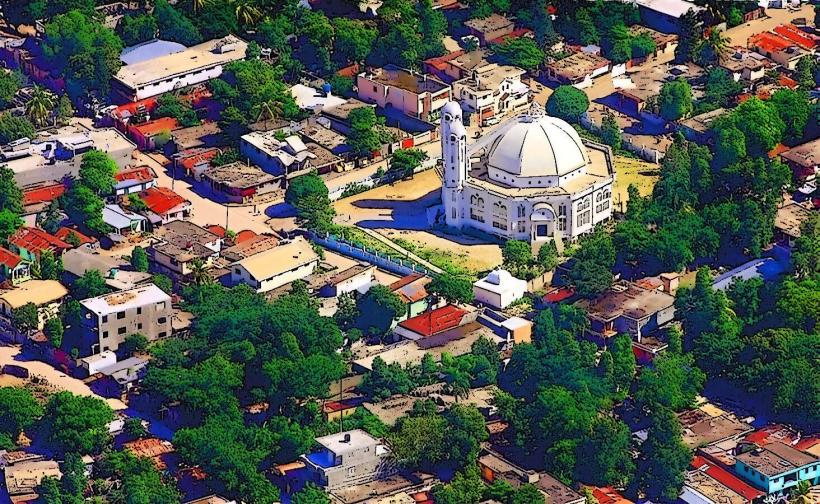

The Artibonite Valley: Hub: Gonaïves.

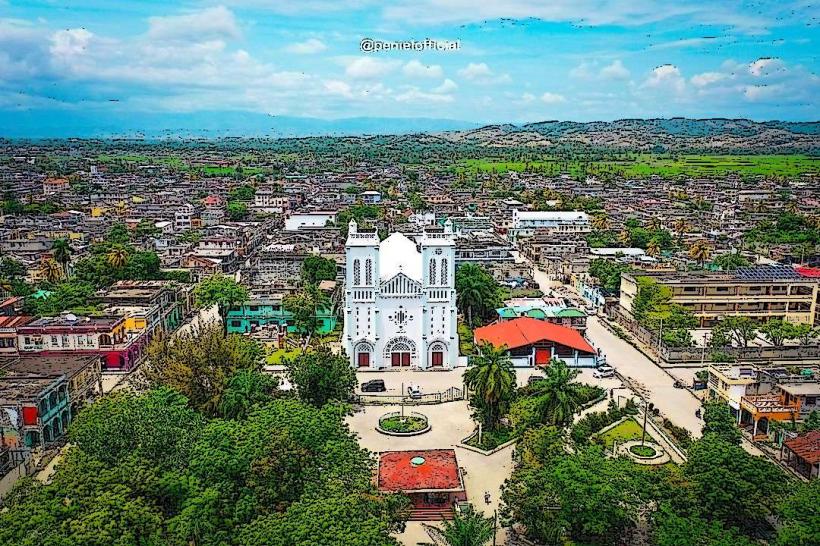

The Southern Peninsula: Hub: Jacmel.

Local Cost Index

1L Water: 115 HTG ($0.87 USD)

1 Domestic Beer (0.5L): 200 HTG ($1.50 USD)

1 SIM Card (10GB Data): 1,200 HTG ($9.10 USD)

Facts & Legends

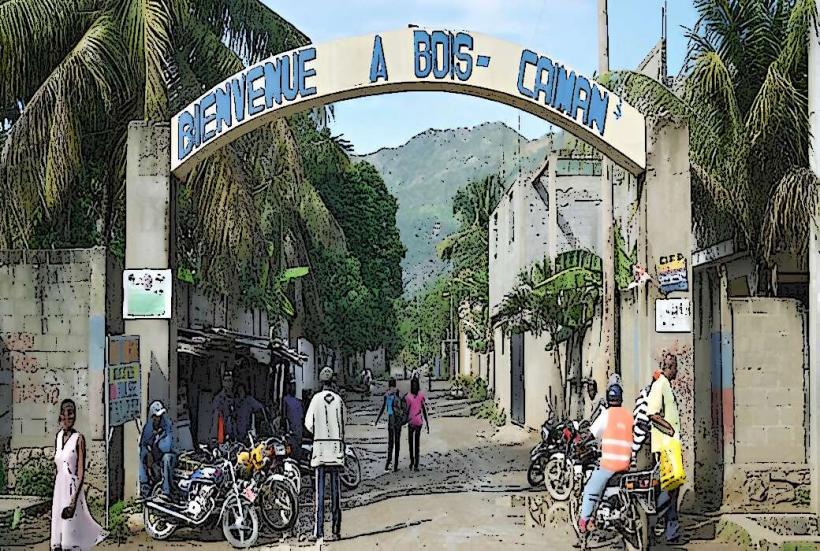

Haiti is the site of the only successful slave revolt in human history that led to the founding of a state (1804). This revolution was sparked by the Bwa Kayiman ceremony, a Vodou ritual in 1791 that served as the catalyst for the uprising against French colonial rule. In folklore, the "Tonton Macoute" (Uncle Gunnysack) is a bogeyman figure who kidnaps disobedient children in a knapsack; the name was later adopted by the notorious paramilitary force under the Duvalier dictatorship.