Information

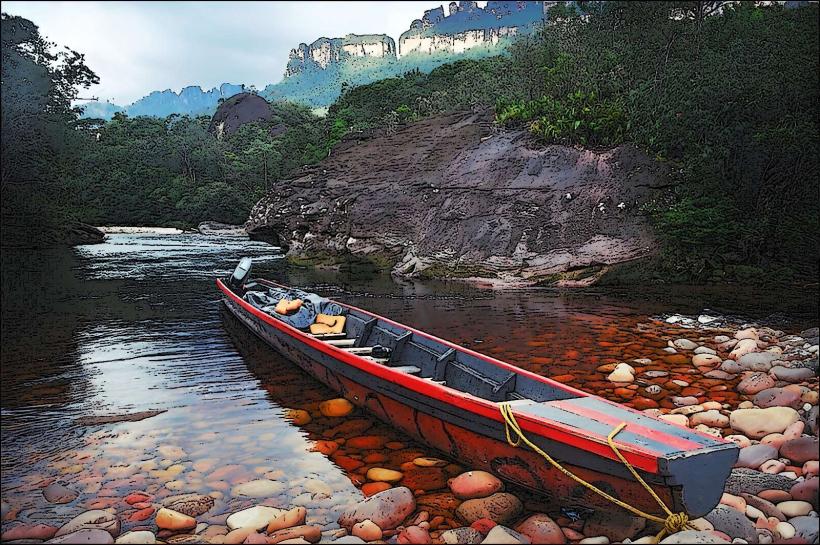

Landmark: Mision de los PemonesCity: Canaima National Park

Country: Venezuela

Continent: South America

Mision de los Pemones, Canaima National Park, Venezuela, South America

Misión de los Pemones is a historical site located within Canaima National Park in Venezuela. It serves as a point of reference for the indigenous Pemón communities and their historical presence in the region.

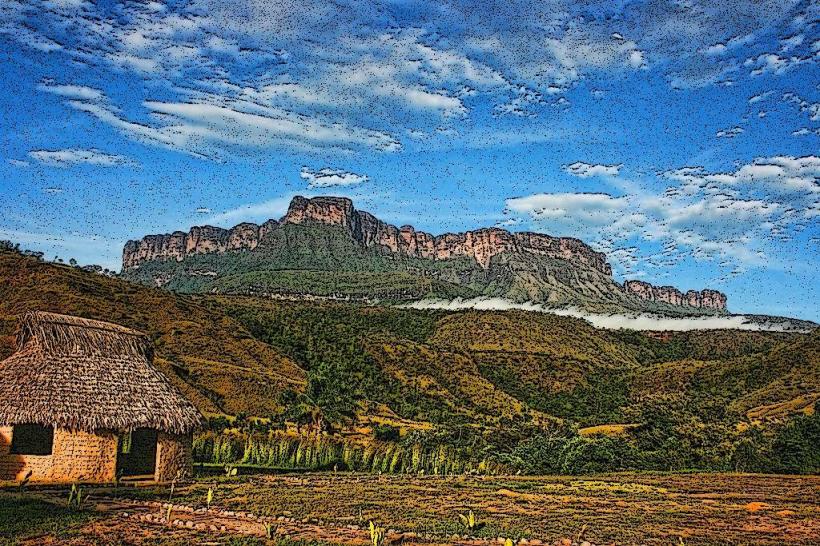

Visual Characteristics

The structure consists of a single-story building constructed primarily from local stone and adobe. The walls are unpainted, revealing the natural earth tones of the materials. The roof is made of traditional thatch, supported by wooden beams. The building's dimensions are approximately 15 meters long by 8 meters wide, with a simple rectangular layout. A small, open courtyard is situated to the west of the main structure.

Location & Access Logistics

Misión de los Pemones is situated approximately 25 kilometers west of Canaima village. Access is primarily via unpaved track roads, requiring a 4x4 vehicle. The journey from Canaima village takes approximately 45 minutes to 1 hour, depending on road conditions. There is no designated parking area; vehicles are typically parked alongside the track. Public transport is not available. Access is also possible by small aircraft landing at a nearby airstrip, followed by a 2km walk.

Historical & Ecological Origin

The mission was established in the early 20th century by Capuchin missionaries with the objective of evangelizing and providing basic services to the indigenous Pemón population. Its purpose was to create a central point for religious instruction and community gathering. The site is located within the Gran Sabana region, characterized by its savanna landscape, tepuis, and diverse flora and fauna.

Key Highlights & Activities

Visitors can observe the architectural style of early mission outposts. Interaction with local Pemón community members may be possible, offering insight into their culture. The surrounding area is suitable for short walks to observe the savanna environment. Photography of the mission structure and landscape is permitted.

Infrastructure & Amenities

There are no public restrooms or dedicated shade structures at the site. Cell phone signal is unreliable and generally absent. No food vendors are present at the mission itself; provisions must be brought from Canaima village.

Best Time to Visit

The dry season, from December to April, offers the most accessible road conditions. The late afternoon, between 3:00 PM and 5:00 PM, provides optimal lighting for photography due to the angle of the sun. Mid-morning can be hot with direct sunlight.

Facts & Legends

Local Pemón oral tradition speaks of the mission as a place where ancient spirits of the land sometimes manifest, particularly during periods of heavy rain. A specific legend recounts a hidden spring near the mission, said to have healing properties, though its exact location remains unconfirmed.

Nearby Landmarks

- Canaima National Park Visitor Center (25km East)

- Salto El Sapo (28km East)

- Auyán-tepui Base Camp (40km North)

- Laguna de Canaima (25km East)