Information

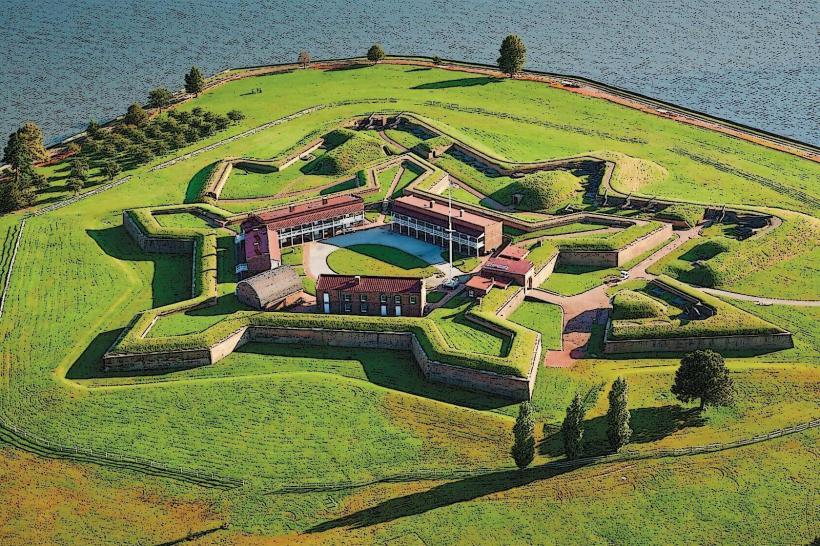

Landmark: Hampton National Historic SiteCity: Baltimore

Country: USA Maryland

Continent: North America

Hampton National Historic Site, Baltimore, USA Maryland, North America

Overview

In Towson, Maryland, the Hampton National Historic Site maintains one of the nation’s most remarkable 18th-century estates, giving visitors a vivid glimpse into early American life-its brick mansions, intricate architecture, and layered social history, likewise the site shares the tale of a wealthy family and of the enslaved African Americans whose hard work-swinging hammers, tending fields-made the estate thrive, moderately Captain Charles Ridgely founded the estate in 1745, and for seven generations-through wars, hard winters, and changing times-it stayed in Ridgely hands until 1948, to boot at its height, Hampton sprawled across about 25,000 acres-wide enough to take hours to trek-ranking among the largest private estates in the country, not entirely The property operated as both a plantation and an ironworks, turning out crops and heavy iron goods-wagon wheels, plows-vital to the economy and the war effort.safeOver the years, Hampton housed hundreds of enslaved African Americans, tending crops under the sweltering sun, laboring in the ironworks, and serving in its kitchens and halls, meanwhile this site stands out for one of the largest recorded manumissions in Maryland’s history-over 300 enslaved people were freed when Charles Ridgely III died-though later generations kept slavery in site.At the heart of the site stands Hampton Mansion, its brick walls and tall windows dating back to 1790, at the same time at the time, it was the biggest private home in America, a sprawling estate that showed off the Ridgely family’s wealth and standing.As far as I can tell, The mansion stands as a Georgian masterpiece, its balanced lines, perfect proportions, and crisp classical trim catching the afternoon light, what’s more captain Charles Ridgely personally drew up the mansion’s plans, while master carpenter Jehu Howell supervised every beam and nail as it rose from the ground.The walls, made from rubble stone pulled straight from the estate’s own quarry, are coated in stucco etched to gaze like precise ashlar blocks-an aged trick that gave the mansion a stately, almost regal air, after that the mansion’s design follows the classic five-part Georgian layout, with a central block flanked by two identical wings, each linked by narrow passageways like slender bridges.The house boasts a Palladian window-a wide, three-part design with a graceful arch in the middle-and an octagonal cupola perched on the roof, where you can take in sweeping views of the estate, as a result inside, the rooms glowed with polished wood panels, ceilings laced in delicate plaster patterns, and furnishings brought in from far-off places, fairly The rooms were meant to dazzle guests and make gatherings flow easily, from lively dinners in the polished mahogany dining room to quiet chats in the velvet-draped parlor, as well as once sprawling across 25,000 acres, the estate has shrunk to a 62-acre heart, where restored formal gardens bloom beside wide, open lawns.In a way, The formal gardens, laid out in the 18th and 19th centuries, feature crisp geometric patterns, stepped terraces, and bursts of ornamental blooms, subsequently the gardens showcase the Ridgely family’s style and deep knowledge of plants, with winding paths and a quiet bench beneath flowering magnolias.Scattered across the grounds stand several state champion trees-towering giants with deep, gnarled bark-celebrated for both their sheer size and their centuries-antique history, meanwhile farm and Outbuildings: Hampton once bustled as both a working plantation and an industrial site, and a few original structures still stand-weathered barns with creaking doors among them.You’ll find barns and stables, a chilly ice house, vivid greenhouses, and a full dairy complex, meanwhile these buildings show just how many different kinds of work take spot on the estate, from repairing gates to tending the rose garden.One of Hampton’s most striking features is its original slave quarters-weathered brick walls that still stand-making it one of the rare plantations in the country where these buildings have survived untouched, to boot these cramped quarters reveal powerful glimpses of what life was like for enslaved people-the dim light, the worn floorboards, the silence between footsteps.The slave quarters are plain, no-frills buildings of brick or weathered wood, built to serve a purpose, not to provide comfort, what’s more most have just one or two rooms, furnished with little more than a bed and a chair.The National Park Service, working with partner groups, offers programs and exhibits that share the stories, strength, and lasting contributions of enslaved African Americans on the estate-like the worn tools they once held in their hands, meanwhile it covers their work in the fields, forging iron, tending homes, and bringing neighbors together.Hampton wasn’t just a sprawling plantation; it bustled like an industrial hub, with the clang of blacksmiths’ hammers echoing across its grounds, as a result the Ridgely family ran an ironworks on the estate, its roaring forges playing a key role in the War of 1812.Actually, Ironworks: The foundry turned out cannonballs, cannons, and other supplies vital to the American war effort, their fresh metal clanging as workers hauled it from the forge, in turn both enslaved workers and free laborers ran the roaring furnaces, pounded metal at the forges, and kept the manufacturing floors humming.The iron from Hampton fueled Maryland’s economy and helped supply weapons and tools for both local and national defense, while hampton, now a National Historic Site, is cared for by the National Park Service, which keeps its history alive and open to visitors-right down to the creak of its historic wooden floors, to some extent The visitor center is open Thursday through Sunday, with exhibits to explore, maps you can unfold, and guided tours that bring the site to life, on top of that you can wander right in without paying a dime.Guided tours take you through the mansion’s sweeping columns, the Ridgely family’s storied past, and the harsh realities faced by the enslaved people who lived and worked there, in turn all year long, the site hosts special programs, from lively historical reenactments to hands‑on workshops where you can smell fresh ink on classical‑style prints.The site welcomes visitors with disabilities, offering parking spaces that are given out on a first-come, first-served basis-view for the clearly marked spots near the main entrance, likewise the gravel paths winding through the mansion grounds and gardens are kept clear so it’s easy to stroll without watching your step.Today, Hampton National Historic Site stands as a layered symbol of America’s past-its grand stone walls speak of wealth and industry, yet they also hold the shadows of enslavement and the stirrings of social change, in addition the site offers a compelling locale to learn, prompting visitors to consider how wealth was built on enslaved labor and how the people who lived and worked there endured hardship-like long days in sweltering fields-through remarkable resilience.Visitors leave Hampton with more than just admiration for its early American architecture and grounds; they carry away a vivid sense of the lives once lived there, like laughter echoing through an aged parlor, then the site sparks conversations about slavery and freedom, and how that history still shapes life in America today-like echoes in a courthouse hallway.

Author: Tourist Landmarks

Date: 2025-10-06