Information

Landmark: Nhabe MuseumCity: Maun

Country: Botswana

Continent: Africa

Nhabe Museum, Maun, Botswana, Africa

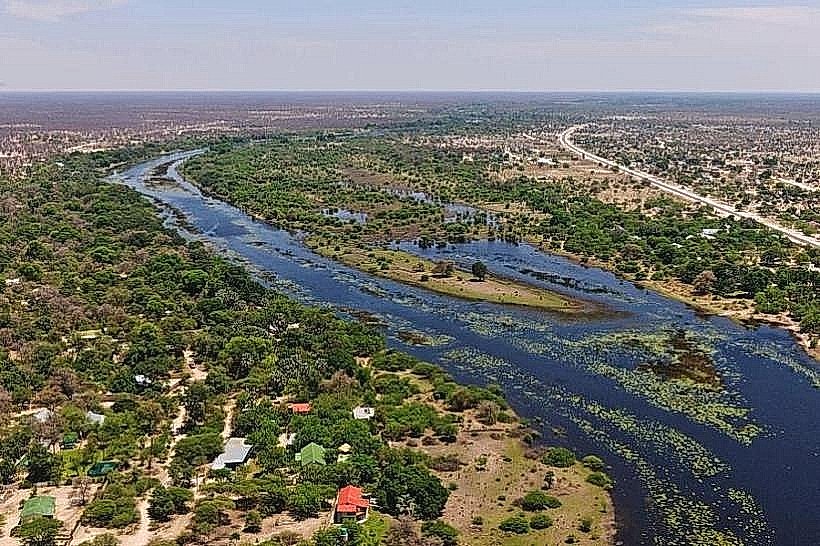

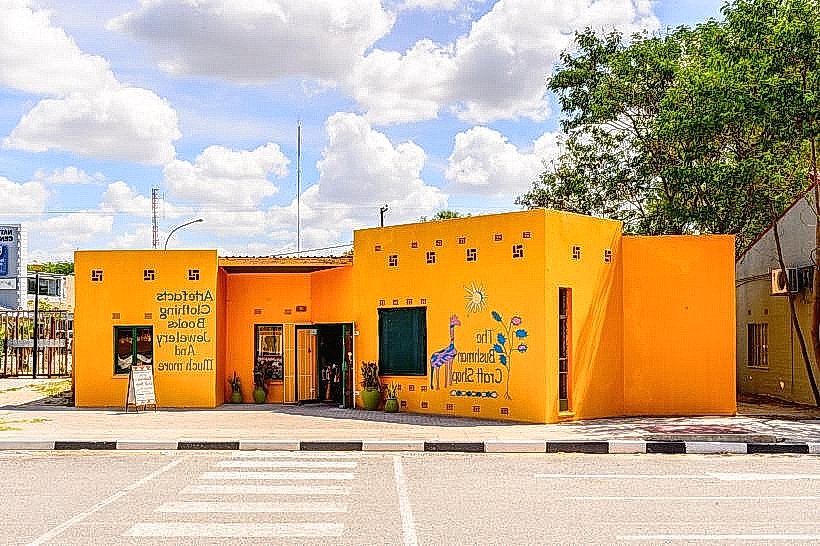

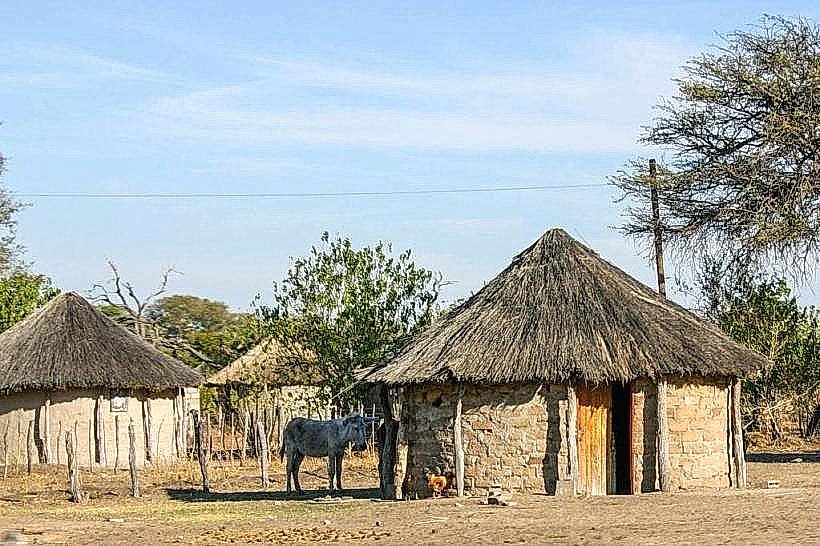

The Nhabe Museum is a cultural institution located in Maun, Botswana. It serves as a repository for the history and heritage of the Okavango Delta region.

Visual Characteristics

The museum building is a single-story structure constructed from locally sourced red brick. It features a corrugated iron roof and has a simple, rectangular design. The exterior walls are painted a neutral beige, and the entrance is marked by a wooden door with a small, attached sign displaying the museum's name.

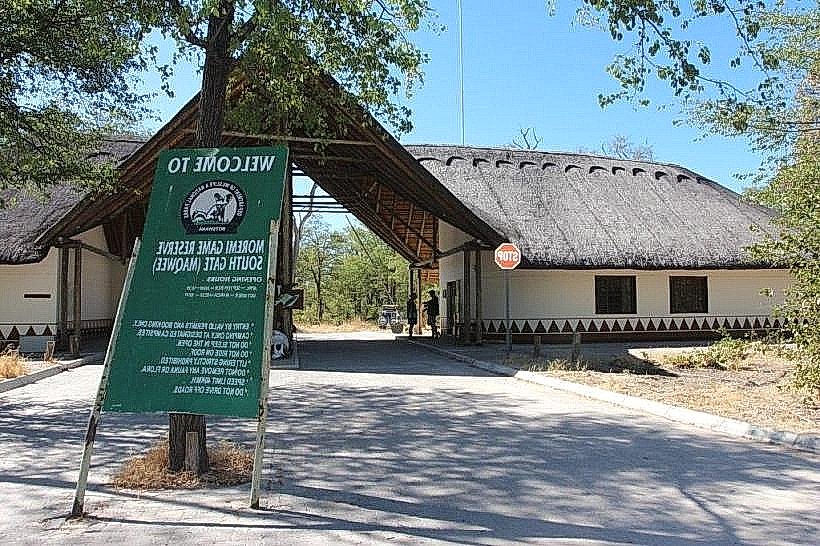

Location & Access Logistics

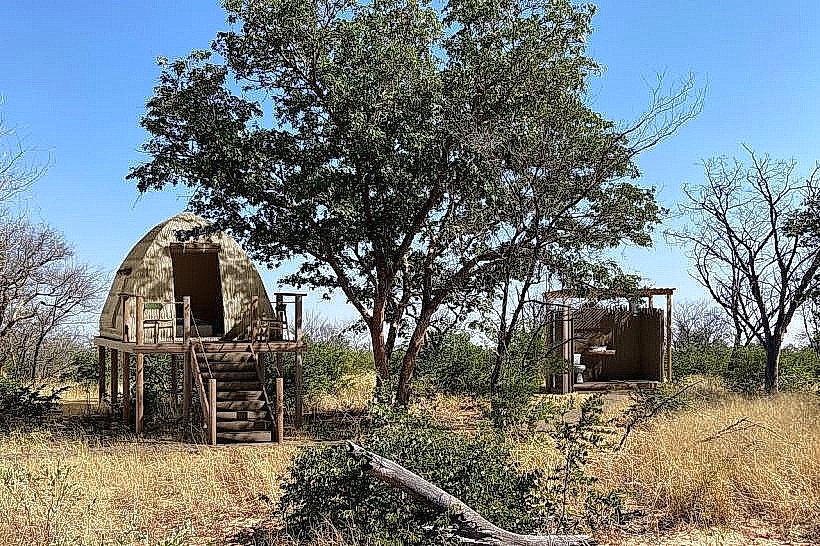

The Nhabe Museum is situated approximately 1.5 kilometers south of Maun's central business district. Access is via the A3 road, turning onto Matlapana Road. Parking is available on-site in a gravel lot adjacent to the building. Public transport options include local combi-vans that run along the A3; disembark at the Matlapana Road junction and walk the remaining distance.

Historical & Ecological Origin

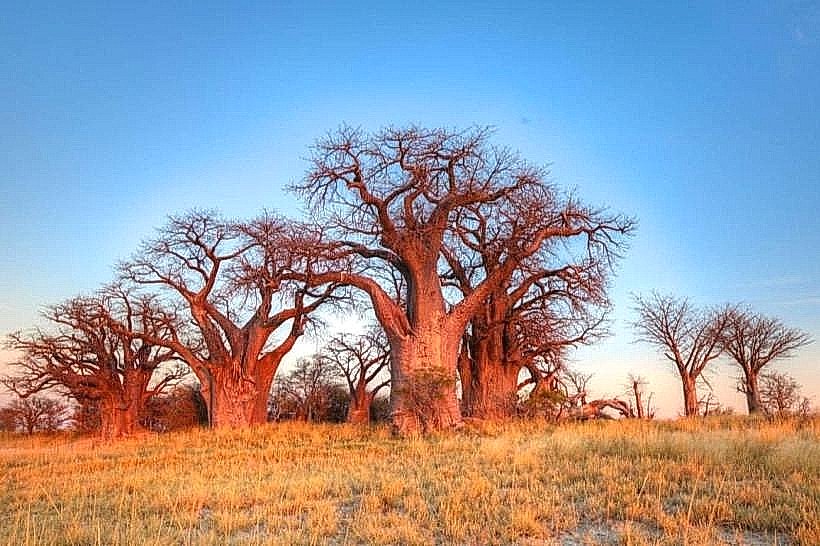

The museum building was originally constructed in the 1970s as a community center. It was later repurposed and opened as the Nhabe Museum in 1997 to house and display artifacts related to the Tswana people and the natural history of the Okavango Delta. Its purpose is to educate visitors about the region's cultural and environmental significance.

Key Highlights & Activities

Visitors can view exhibits detailing the traditional lifestyles of the Batawana people, including displays of pottery, beadwork, and agricultural tools. The museum also features information on the unique ecosystem of the Okavango Delta, its wildlife, and conservation efforts. Informational pamphlets are available at the reception desk.

Infrastructure & Amenities

Restrooms are available inside the museum. Limited shaded seating is provided outside the main entrance. Cell phone signal (4G) is generally reliable within the museum premises. No food vendors are located directly at the museum; however, several small shops and eateries are situated within a 500-meter radius in Maun town.

Best Time to Visit

The museum is open daily from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM. The best time of day for visiting is during the cooler morning hours, between 9:00 AM and 11:00 AM, to avoid the midday heat. Any time of year is suitable for visiting, as the exhibits are indoors.

Facts & Legends

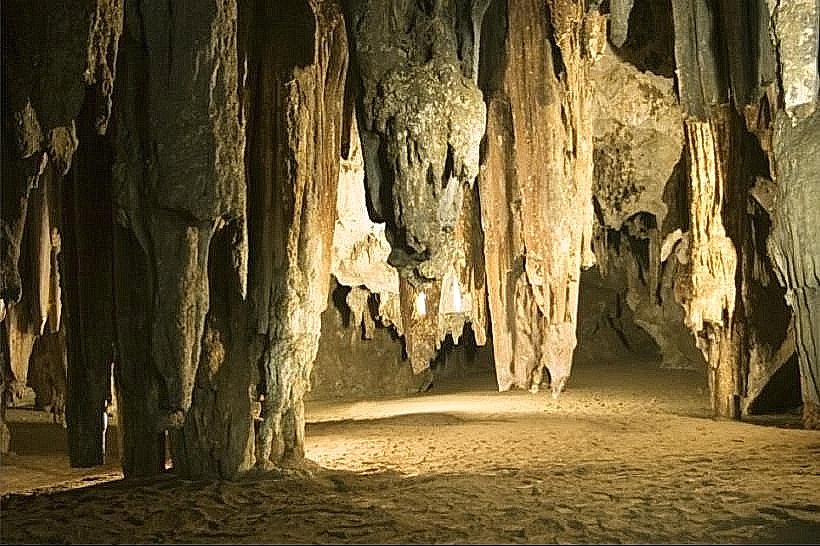

A notable artifact within the museum is a collection of traditional hunting tools, including bows and arrows, used by the San people who historically inhabited the area. Local lore suggests that the spirit of the Nhabe River, a now-dry seasonal riverbed, still influences the local weather patterns.

Nearby Landmarks

- Maun Main Mall - 1.2km North

- Okavango River Lodge - 1.8km Northwest

- Thamalakane River - 0.8km West

- Botswana Police Service Maun Station - 1.0km North